To write killer stories you have to learn three things. The first is what stories do. Once you know that, you’ve got to learn how stories do the things they do.

What’s required to generate suspense in a reader? Curiosity? Attraction? Mirth? Rooting interest? Sympathy? Dread? Wonder? Insight? How does it all work?

How DOES it all work?

Well, emotion is generated in a story the same way it’s generated in real life. The big difference is that in a story our emotions are guided along by the text. This is NOT to say that the author is a puppet master. Nor is it to say that you can write a story with cold calculation for effect. In fact, I don’t believe that’s possible becasue to write killer stories you have to follow the zing–you have to feel your way through it. Nevertheless, emotion follows the same process. So how does emotion work?

I’m not going to get technical and long-winded here. If you want to know details, I suggest you read the following texts: Feeling Good by David Burns (first 50 pages), The Science of Emotion by Randolph Cornelius, and Deeper Than Reason by Jenefer Robinson (through chapter 5). However, there are a few key insights you must take away.

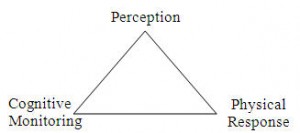

Very simply put emotion is a process where the mechanisms of perception, physical response, and cognitive monitoring constantly give feedback to each other.

You perceive a situation. You immediately get a physical response. Your cognitive monitoring kicks in and futher assesses the situation. This affects your physical response. Which in turn affects your thoughts.

For example, I live in the mountains so we regularly see snakes. Some of these are rattlesnakes. So I recently walked out into the yard. I stepped on something in the grass. Snake! I immediately got a physical response. I skipped away, my heart palpitated. My cognitive monitoring kicked in and I noticed something odd. I looked closer. It was the garden hose! My fear turned to relief and mirth.

Perception, response, monitoring, response, perception, response…

Thoughts lead to emotions. And so when you’re trying to figure out how to generate an emotional effect, you have to think about the kinds of thoughts and situations that generally produce that effect.

Clarity & Believability

However, before we get into specific effects, you need to know two things. First, if the situation isn’t clear or believable, you’ll get an emotion you don’t want. Mostly confusion, boredom, or disgust. So your writing must be clear and believable.

Here’s an example of how necessary clarity is. Look at this picture.

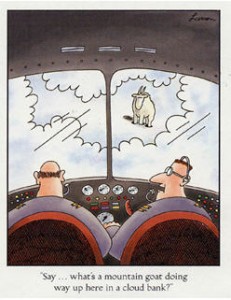

Your response was probably, huh? The joke can’t work because you don’t know what the heck is going on. Look at the next picture.

You may not laugh because this isn’t your type of humor. But you didn’t even have the chance to laugh until you understood the situation.

Your stories must provide a clear situation–what’s happening, to whom, why. Without clarity you will only generate confusion and boredom. And then the reader says, “Next,” and your story goes back on the shelf or into the trash.

What about belief?

Think about the garden hose example above. As soon as I saw through the snake illusion my fear left me. It was immediate. Likewise, as soon as readers see through the writing, don’t believe your characters would act like they do, can’t buy the situation. As soon as it gets hokey–even in humorous situations–the emotion leaves.

We’ll talk about things that increase clarity and belief later. For right now, just know they are critical. The thing you need to know at this point is that you generate emotion about a situation in a story just as you do about a situation in real life. You also need to be on the look out for things that trigger your emotions in real life–fascination with a character, fear, anxiety, curoisity, etc.–because you’ll be using those in your stories.

So what parts make up the situation or story? What are the raw materials you have to work with? That’s the topic of the next lesson.

You said, “Thoughts lead to emotions.” I think I might have taken this the wrong way, at first. You are not talking about the character thoughts and emotions; you’re talking about the READER thoughts and emotions. I most generally follow the scene-sequel method of story structure, and I thought that required the characters to react in a very specific order:

1. Stimulus, some action or single event, elicits an

2. Emotional response, and when the character regains rational control again he or she experiences

3. Thoughts, which lead to a

4. Plan and finally the character’s next action.

For example, this violates sequential order:

A knock came to the door. Joe thought, I wonder who it could be? He jumped from his easy chair, heart racing.

This seems clearer, to me:

A knock came to the door. Joe jumped from his easy chair, heart racing. He thought, I wonder who it could be?

But, if understand correctly, you’re saying 1) something happens on the page, 2) the reader has thoughts, and 3) finally feelings about it.

That might take some getting used to, trying to understand that the character and reader are going to have two different sequential orders of reaction.

Sam,

Yes, indeed. Great insight. The SiR order you mention, Stimulus-Internalization (if necessary)-Reponse, is critical to make the story clear to the reader. In many instances the reader will feel along with the character. But not always. Imagine a little girl swinging at a park bordered by a wood. You present to the reader that she’s there alone. Her big brother went off to get ice cream down the road. And there’s a predator standing not twenty yards away in the trees. It could be a serial killer, some paranormal creature, maybe a wack job that wants to rape her. The girl is simply swinging away. The reader’s response, their emotion, is going through the roof.

We must never mistake our job as making a character feel something.

Our job is to tell a story to the reader that takes the reader on an emotional ride. That’s what they’re paying us for. That’s what we love.

So the SiR sequence is critical to help keep the story clear for the reader so that they can have the response. Search for “Vivid and Clear” on the site, and you’ll find a bootleg recording of a presentation on that and some other techniques to keep the story clear SO THAT the reader can respond.

I guess the other thing is that we can’t force the reader to respond. All we can do is present what I call the “antecedents.” I should probably just call them the reader stimulus because that’s what they are. The key is that what we present doesn’t affect all readers the same way. That’s why some people love Harry Potter and others pass over those books like they are something weird with kale in it.

Oh, wow! Thank you for pointing me to the “Vivid and Clear” videos. I’ve studied Jack Bickham’s and Dwight V. Swain’s instructional books (I’m sure you could tell), but your presentation took the next step, especially concerning details. Brilliant.

Glad you found it helpful 🙂