I’m going to talk a bit about some murderers in Detroit, Jesus, and a couple of books I recently read that I think are just awesome.

MURDER

So, the murderers.

So, the murderers.

Let me start by asking this question: can you establish the truth in a court of law?

Is that what the judge and jury are deciding? The Truth, with a capital T?

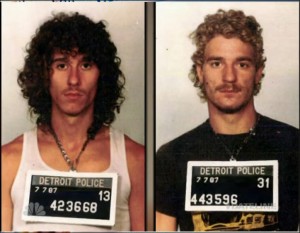

Think about Tommy and Ray Highers, brothers from Detroit. They were convicted of murder. Open and shut case. No parole. They were two nasty buggers who shot a man down over some dope.

But then twenty-five years later (last year, in fact) they were back in court because new evidence had come to light that undermined the original conviction. For the curious, this fascinating Dateline episode reveals the amazing way the evidence came to light and what happened because of it: http://www.nbcnews.com/dateline/full-episode-graduation-night-n72666. Watch it. You’ll be happy you did.

So the Truth. Capital T. Can you establish that in a court of law?

No.

What the justice system does is try to determine which story about the evidence available is the most convincing.

It’s about telling and judging stories.

There are many types of evidence folks use when telling their stories. Some of it is very strong. Some is so unreliable, like hunches and hearsay, that the court won’t even allow it to be presented.

Whatever the evidence, the fundamental nature of this is that you can often tell a number of different stories using the same set of data, the same evidence. Sometimes the stories are variations with minor differences. Sometimes the stories are radically different.

It’s like having only some of the pieces of a 100 piece puzzle. You look at the four, twenty, or thirty pieces you have and imagine what the rest of the puzzle looks like. And then you invent something that seems reasonable.

You invent it.

And if that story meets certain standards of proof, then our system allows the authorities to take certain actions. If the standard of a “reasonable suspicion” is met, it allows a police officer to stop someone. If the standard of “probable cause” is met, a higher standard than reasonable suspicion, an officer can arrest you. If a jury in a criminal case decides the defendant is guilty “beyond a reasonable doubt,” an even higher standard of proof, then the justice system authorizes the authorities to sentence the defendant.

But at no time does the system seek to establish the absolute truth, the truth with a capital T. It only seeks to establish some level of probability that the story being told about the evidence is true.

All of this is made more complex because what’s “reasonable” is based on other people’s opinion. We have guidelines and rules to help folks be “reasonable.” But reasonableness is still affected by culture, background, history, etc.

It’s still opinion.

OTHER PUZZLES

What other realm of knowledge works like the justice system and consists of inventing stories about missing parts of the puzzle?

Well, history does.

In fact, if you think about it, history is what courts do. The processes and principles of our justice system guide everyone involved in how they go about telling the stories that make up that specific type of history.

And all historians (lawyers, judges, and juries included) have no means of establishing the absolute truth.

They can’t use science. Science requires you conduct experiments and reproduce results. But how is a historian going to reproduce the same events? What, they’re going to get Lincoln shot all over again and let the rest of us watch it? Dang, John Wilkes Booth did shoot the man. We all saw it happen down in the lab.

Sure, they can use science to date a manuscript, or determine what something is made of, or establish some other fact. But all science is doing is providing facts about the pieces of the puzzle you have. About the claims the evidence makes.

But science can’t fill in the missing pieces of the puzzle. It can’t tell the story. The historian has to invent the story that makes the pieces all make sense.

And then the rest of us determine if that story, that sketch of the full puzzle, is reasonable.

But that isn’t all there is to it.

STANDARDS OF PROOF

Think about conspiracy theories like the ones that claim that the US government perpetrated the 9/11 bombings. Conspiracy theorists are practicing history. They are inventing a story that seems to fit the evidence available to them.

But what happens when you have only five or ten pieces of a 1,000 piece puzzle? What happens when you don’t thoroughly vet the evidence? What happens when someone screws around with the evidence? And I’m not just talking about tampering or invalidating it by thoughtless handling (contaminating DNA, for example). Folks with the best intentions have biases. In fact, we all have biases that lead us to include and exclude various pieces of evidence based on whether they support or oppose the ideas we want to believe.

Jonathan Haidt explains these biases in his excellent book The Righteous Mind. He explains that with things we want to believe, we often use the standard of “Can I Believe It”? We look for anything at all that would allow us to believe our position. If we find it, even if it’s flimsy, we discount all the other evidence that may point another way and conclude we have met the burden of proof for our view.

For things that we don’t want to believe, we often use the standard of “Must I Believe It”? When falling prey to this bias, we look for anything at all that would undermine the thing we don’t want to believe, even if that evidence is flimsy. If we find it, we ignore all the other evidence, even if there’s a mountain of it pointing another way, and claim we have met the necessary burden of proof.

In court there are all sorts of procedures and standards that need to be followed to help us avoid invalidating evidence or falling prey to our biases. Those procedures and standards don’t remove all risk. But they do remove a lot.

Which court system would you want to be processed through? The current American justice system or the medieval witch trials?

Oh, for sure I’d want to be someone accused of witchcraft back when a claim of “I saw her as a witch in my dream” was admissible, as was the test of poking a mole on the accused’s body with a needle to see if said witch flinched enough. I’d be so happy to go back to the days when a confession obtained by torture was incontrovertible evidence.

So when practicing history, it’s important to have some guidelines, some rules to establish which bits of evidence are more likely (not guaranteed, but more likely) to be reliable. And it’s important that when folks tell their story, they not only share the evidence, but also all the assumptions they’re making.

JESUS

Where does Jesus of Nazareth come into all of this?

Well, Jesus has affected the world more than any other person who has lived on it. The stories we tell about him (the history we have practiced about him for the last 2,000+ years) have changed the world. And those stories will continue to affect us, especially folks in Western cultures, on everything from foreign policy to which clothes think are fit to be worn in public.

Who was Jesus? Did he really exist? Was he a god? What did he really teach? Have his teachings been changed?

These are all fundamental questions. And for the last two-hundred years historians have been re-examining the pieces of the puzzle, finding new pieces, and telling new stories to explain it all.

Some of these historians believe in Jesus as a god. Some don’t. Either way, the conversation is fascinating.

I just read three historical books about Jesus that were awesome. AWESOME. Not because I agreed with all of the author’s conclusions, i.e. his stories. I don’t. But because of the way he practiced his history. The way he told his stories. And because what he shared gave me new insights to my stories about Jesus.

The three books, all by Bart D. Ehrman, a professor of religious studies at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, are:

- Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why

- Jesus Interrupted: Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (And Why We Don’t Know About Them)

- Did Jesus Exist? The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth

I’ve read the Bible many times, and I’m a believer. Of course, the question is a believer in which story?

What Ehrman so engagingly makes clear is that there have indeed been many stories about Jesus. In fact, the gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) and the writings of Paul (most of the rest of the New Testament) seem to all portray a different man and message. Not only do they say things that flat out contradict each other on some details, but if you look at each book separately, each author seems to have a slightly different take on Jesus.

Furthermore, it appears that what we now have has changed over time. For example, it seems the last twelve verses of Mark were not in the oldest manuscripts. There have been other changes. One of the more notable ones occurs in John 5:7-8.

Our earliest texts say:

“For there are three that bear record, the spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one.”

But later texts say:

“For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness in earth, the spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one.”

Nowhere else in the New Testament do we have anything that states that creedal doctrine so explicitly. Did John write that? Or was the extra material added to make the idea of the trinity scriptural?

And what do we make of the fact that we have no manuscript that dates to anywhere close to when Jesus lived? We have some small fragments of manuscripts with a few verses of John, Revelation, and Matthew dated around 150 AD. But the oldest manuscripts we have that contain the majority of any of the gospels are for the gospels of Luke and John, and these are dated around 200 AD. The oldest manuscripts with the full New Testament are dated around 350 AD.

That’s more than 300 years after Jesus died!

Have you played the game of telephone? Are we sure that the oral traditions that were written down weren’t changed? What happened to the books mentioned in the Bible that we don’t have now? For example, Jude mentions a prophecy of Enoch that we don’t have in our current Bible. Are we sure that the copyists didn’t add to the text like it seems some did to John?

And what about the term “Christ”? It’s actually the Greek word for “messiah” which just means one anointed with oil to perform a special service for god. Christ wasn’t Jesus’s last name. It was a title: Jesus the anointed one.

The anointed ones in those days were kings and prophets and priests. It appears most of the historical sources suggest that a “messiah” to the Jews of that time was someone who would throw off foreign rule and establish the kingdom of Israel as David had. In fact, there were a whole bunch of people who claimed to be messiahs. Here’s a nice list: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_Messiah_claimants.

Judas Maccabeus was considered a messiah because he threw off Greek rule in 164 BC. But then around 63 BC Israel was taken over by Rome. And Rome wasn’t too keen on revolts, so around 4 BC they crucified Judas the Galilean for claiming to be the messiah, the king of the Jews. Crucifixion, it seems, was the punishment reserved for seditionists. They crucified Jesus and a whole bunch of other guys claiming to be the king of the Jews. And their crimes were written on a board above them, which is why they hung the words “King of the Jews” over Jesus’s head on the cross. Here’s the criminal, and here’s his crime. These other messiahs were not claiming to be a god that came to earth to atone for sins, but anointed by God to throw off foreign rule and establish his earthly kingdom again.

Jesus talks a lot about the kingdom of God. Was Jesus just another one of the seditionists?

Ehrman examines these and many other questions as a historian, providing all sorts of insights.

But the fabulous thing is that he doesn’t just tell his story. He gives his evidence. Exposes his assumptions. And in all three books he explains the guidelines or “rules” historians use to when trying to determine which stories are more likely and which evidence is more reliable.

I was enlightened, challenged, and delighted. I learned things about Jesus’s life and times that have helped me understand what I read in the Bible better.

LIMITS

Of course, the historical method has its limits.

Historians, because they are looking for explanations (stories) that are more probable, automatically select against things that are improbable. They exclude miracles. They exclude any story that says Christ was actually resurrected. They may establish that a lot of folks thought he was resurrected, but they don’t have any methods to establish something like a resurrection actually occurred. And so they ignore it. Historians exclude modern revelation. If someone today were to have a visitation from Jesus as Paul did, the historians would exclude that.

But we all know that truth is sometimes stranger than fiction. We all know that sometimes the less likely thing is exactly what occurred.

Historians are looking for what is most probable. Not what actually happened. Because they can’t go back and time and verify their story.

Excluding “improbable” things changes the types of stories the pieces of the puzzle support. For many of us, me included, we do accept evidences many historians don’t as pieces of the puzzle. And because we have these pieces, we’re able to tell different types of stories.

The cool thing about Ehrman is that he explains this. He’s not trying to hide anything. Instead, he’s explaining how to approach the Bible from a historical point of view, and where the principles of the historical method lead him.

And I have found that those methods in his hands have a lot to offer.

If you’re someone who is interested in religion–as a believer, agonistic, or atheist–you will love these books. Ehrman himself was once an ardent believer, but is now agnostic. However, his respect for believers, including other scholars in his field who believe in the divine Jesus, comes through loud and clear. Ehrman has no axe to grind. He is simply sharing the stories of Jesus that make sense to him and many other historians. And he does it in a very interesting and easy-to-read style.

If these books sound like something you want to try, I’d start with Misquoting Jesus, move to Jesus Interrupted, and then finish with Did Jesus Exist? And if you enjoy those, let me recommend two more of Ehrman’s books. The first is The Lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot: A New Look at Betrayer and Betrayed, which looks at the discovery and content of a very ancient manuscript that calls itself The Gospel of Judas. The second is Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew, which explores the variety of Christian faiths that existed in the few hundred years after Jesus’s death.

Happy reading!