I want you to think about Ed Smylie, who helped save the Apollo 13 astronauts with his duct tape contraption. What if the authorities had come to Ed, but instead of saying, “Look, we need to fit the round CO2 scrubbers into the holes for the square ones,” they’d said, “We want you to do something; it involves thinking.”

Ed would have blinked. Waited. “Yeah?”

“That’s it. Something. A lot is riding on this.” And then maybe they urged him on with a significant wave of their hands.

Can you see Ed at this point?

“Sure.” He’d say. “I’ll get right on that.” Then he’d wonder who put these guys up to this practical joke.

Do you see how impossible it is when you frame things that way?

To come up with solutions, you have to have a clue about what it is you’re trying to do. Even if it’s just a rough idea. It doesn’t matter if you’re trying to fix a space ship, roast hotdogs, or write a story.

Once we have a rough idea of what we want to accomplish, the mind automatically kicks into gear to perform its wonders. Until we do that, we’re going to be like Ed in the example above—staring at a blank wall, wondering if our superiors aren’t a bit cuckoo.

So what are we trying to do?

Think about your reader. Is it a woman? A teen? A crazy dude? Do you remember my book tour with Larry Correia in 2009 and the guy who, during a booksigning / doughnut party at a Phoenix Barnes & Noble, proclaimed my book to be true? Aliens really were eating our souls and enslaving humanity. They were lizards living in the hollow portion of the earth.

The point is: what are your readers hoping your story provides them? In fact, since you’re the first audience, what do YOU want from your stories? Why do you read?

I want you to write down five stories you really like. Movies, TV shows, novels, short stories, plays—I don’t care the genre or type. Just write down five. Do it now. Here are five random stories I like.

- The Incredibles

- The Good Guy by Dean Koontz

- Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

- The Sound of Music

- Runelords by David Farland

This is going to be a powerful exercise for you. It was for me the first time I did it in a class on interior design.

A few years ago, Lovely Wife and I were building a house. We wanted to make our living space sing. We wanted our surroundings to make us happy, but we didn’t quite know how to go about doing that. So we took a class on interior design, hoping to learn the principles involved.

Except when we showed up in the first session and saw the many different design styles, it overwhelmed us. Some styles were ethnic (Southwestern, Asian, French, Gothic, Pygmy), some philosophical or religious (Zen, Feng Shui), many were artistic (Modern, Arts & Craft, Minimalist, Art Deco, College Room Mate ), a lot were mixtures. Some were about making statements and creating moods, some about practicality (here’s a taste of those styles). How in the world were we going to learn this?

Luckily, we had a very perceptive teacher. She knew that most of us were there, not to learn all the styles, but to decorate our own houses. So in our second session, she brought dozens of home magazines. She spread them out on the tables we were sitting at and told us we would go through the magazines. When we found a picture or image we liked, we were to rip that page out and put it in our personal stack. So for about 45 minutes we looked and ripped and looked and ripped. Lovely Wife and I each ended up with a pile of a few dozen pictures.

Then the teacher told us to spread our pictures out in front of us and look for things that the images had in common. Colors, features, design elements.

I spread my pictures out. Lovely Wife spread out hers. And it was like magic. Boom! Right there in front of us. I loved arches and eyebrow windows. Loved dark blues and purples mixed with creams and whites. Loved the color of blond wheat and a navy blue sky. I loved wood. Loved Arts & Craft with a few tweaks.

Lovely Wife’s pile was equally revealing.

The teacher then said, “This is your personal style. This is what’s going to make you happy.” She told us that when designing the rooms in our house, that we should think about their function and merge them with these elements. And if any of us were to work with clients, we’d do something similar with them and find out their wants and likes.

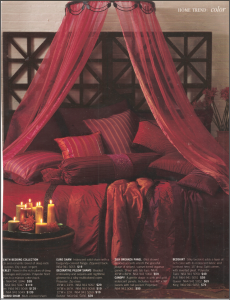

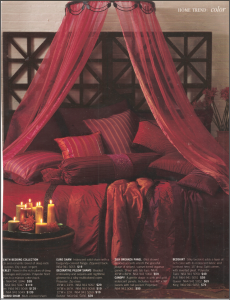

With our styles now beginning to be fleshed out, Lovely Wife and I went to work. Some of her elements and colors overlapped mine. Some didn’t, like her idea of sleeping bliss: a bed with sheer red drapes hanging from some lamp shade contraption in the middle.

I told her I didn’t know if I could keep my man card and sleep in that bed. She decided I should keep my man card, but said she couldn’t sleep in a plain-walled zen room. We compromised. She got textured red on the walls. I got a bed without too many frills. We came up with designs for our spaces that did what we wanted them to do.

But we couldn’t have done this if we hadn’t identified what we were after.

So I’ve adapted that visual art technique used in the design class for our purposes. It’s just as powerful with literary arts. Which is why I want you to write down five stories.

I want you to take a moment and identify what you’re after, in a big picture general way.

I can’t do this for you.

You and I are different. Just like Lovely Wife and I are different. While our tastes may overlap in some places, they’re going to diverge. You don’t want to write my stories. You want to write YOURS.

So write down five stories. Then write down what you really enjoyed, over all, about each of those five stories. You might do this on five pieces of paper. What did you enjoy with each of the main story elements—character, setting, problem, plot, and text? What kind of an experience did they give you? What drew you to them in the first place?

You don’t need to go all crazy detailed on me with this and do a twenty page report. Just hit the highlights. The stuff that will fit on one page without writing in four point font.

When you finish that, step back and look at all five pieces of paper side by side. What common elements do you see? Circle them.

This is your style. This is what, in general, you’re going for.

If you found the exercise insightful, do five more stories. Ten is such a nice number.

I’m going to predict that 99% of the things you identify have to do with what the story did to you. The stories made you laugh, smile, scream, want to fall in love again. They made you curious or jealous or feel some type of desire (be a Ninja king, strong, beautiful). Maybe they gave you insight. Maybe they affected you so profoundly that it changed, if even in a small way, how you decided to live your life.

Stories–the ones people pay money for; the ones people stay up until four a.m. reading with a flashlight; the ones people tell their friends about–make people feel things.

A while back I wrote about this in three parts. I believe the things you’ll read in those short posts, if you don’t know them already, will change how you think about stories. They did for me. And it all begins with lipstick.

- Lipstick

- Getting specific

- My big draws

Okay, I hope at this point you are getting a general idea of why readers pay money to read the stories we create. Why YOU pay money and spend countless hours reading what others write.

This is the first step in being able to produce on purpose, not on accident. This is the first step to becoming the Ed Smylie of fiction—understanding what you, as a writer, are trying to do.

This week, keep your eyes open. Notice what stories do to you. Notice how you feel about different characters and plots. If you feel like taking it farther, notice the effect of different beginnings and ends of novels, chapters, or scenes. Notice the effect of different ways authors describe characters, places, and actions.

Of course, while knowing these general objectives is critical, it’s not enough. You need to know what you’re reaching for with the current story, the current characters, the current plot. How do you translate all this general stuff to the specifics of the story in front of you? Do you have to define everything up front? And what if you don’t know what you want in the current project anyway? What if you are clueless and have nothing but a handful of random ideas that for some reason are generating electrical sparks? What do you do then?

In the next post, I’ll talk more about those questions and where the how-to’s fit into all of this, and then we’ll get into the principles of invention.

For more in this series, see How to Get and Develop Story Ideas