Almost everyone reading this knows what they like in a car. We know what we want a car to do. We can talk about acceleration, voom-voom styling, and handling. Some of us could talk about how engines and transmissions and tires all work together to create those things. We could get really technical.

But how many of us could then go manufacture a tire? Or the paint we’re going to put on the car? How about a windshield?

No?

Well, what about one little bolt? Just a little bolt. Can you do it?

There’s a difference between knowing what a thing is supposed to do, how it works, and actually building it. A lot of people can talk about the first two topics and have no idea at all about the third.

It’s the same with stories.

There are three things we have to learn to write killer stories.

- What a story is supposed to do.

- How the 5 parts of story—character, setting, problem, plot, and text–do that

- How to come up with and develop a story idea in the first place

We authors talk a lot about the second thing. You have books and blogs galore on dialogue, plot, characters, structure, grammar, world-building, setting—you name it. Heck, the big series I wrote last year about the key conditions for reader suspense was all about how story works.

Some of us talk about the first thing. And really there’s no point in blathering on about the how-to’s if we don’t know the what-for’s, which is why I tried to highlight one of the core what-for’s in my series on suspense.

But as important as those two things are, none of it matters if we don’t know how to put it to use. We’re not reviewers or editors. We’re creators. We’re writers—the ones that invent the story in the first place. And let me tell you, knowing how a story works and how to invent one are two very different things.

I didn’t know the principles of invention when I was first starting out. And that gap in my knowledge was one of the things that held me back for years. In fact, I almost gave up my dream of writing stories because of it.

Very early in my attempts to start a career I wrote a story that won an award and $2,000. I was flown out to Cocoa Beach, Florida for a week-long workshop with amazing pros. Was published. And then I went home, finished another story (yea!), and proceeded not be able to finish another thing for five years.

Five years.

FIVE. YEARS!

And I tried.

After five years of failure you begin to wonder if maybe you didn’t get the wrong memo (what am I doing at this empty warehouse?). Your family begins to wonder that as well. You realize life is short and there are a lot of other things you could be spending your time on. You begin to think that only an idiot would spend more time on this. And you’d probably be right.

Unless, of course, you realize that what’s keeping you back isn’t a manifestation of cosmic will. Rather, it’s just a lack of understanding.

That’s what happened in my case. Just a few days before I gave up on all my dreams, the light was turned on for me. I learned some key, but simple, principles of invention that I hadn’t known. You can read the whole story here. After I learned these principles, my production took off like a rocket.

And so what I want to do in this series is share those principles with you. Hopefully, this will unleash your abilities. You might find a huge audience for your stories. You might find only the family dog will stick around to listen to them. The popularity of your stories is a separate matter. But you can’t even find out how big your audience will be if you don’t know how to finish.

So let’s start. A lot of people think that creativity is about passion. When they think of creativity, they think of someone like this.

Look at him. Brushed velvet jacket. Beard. Rakish devil-may-care hair. And that gaze. Look at that gaze! It’s full of passion. It’s coming off him in waves. In fact, we all know his inner world is a vast tempestuous sea of passion that sends ideas crashing in great surges onto the rocky beaches of his soul. And those earthly forces cannot be contained. No, he must write them, write them, write them. That’s the face of a man who will channel fire onto the written page because if he didn’t, he would surely burn.

Or maybe not.

Maybe creativity is about being like this guy.

Hello, Malcolm Gladwell. Look at him. There are so many ideas in that great blaze of brains they trip over themselves trying to get out. There are so many they kinked his hair with their electric heat. Oh, fecund mind!

Or maybe not.

Maybe creativity is all a function of being blessed.

Or maybe it’s about alcohol (or some other chemical). After all, isn’t that how Ernest Hemmingway did it?

Or it’s about being mentally unstable.

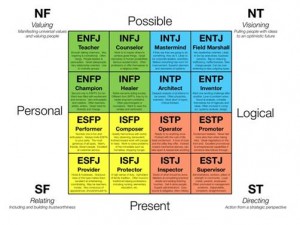

Or it’s about having the right personality type. I remember the day of woe when I learned that I was an ENFJ but that the “natural” writers were all ISFPs!

Or it’s about being eccentric.

Or it’s none of that. It’s about being born to it.

Right? All of those things are what creativity is about. And if, as so clearly demonstrated by those pictures, you don’t have passionate hair, well then, forget about it. Except here’s Larry Correia, a New York Times bestseller, who has no passionate hair whatsoever.

Huh?!

How could that be?

Here’s how. All those ideas above about creativity–they’re rubbish. Creativity has nothing to do with passion or hair or whether you wear Argyle socks.

Nothing.

Let me show you the face of creativity.

That is Warren Ellis. Warren is my brother-in-law, except when he’s not (do not ask me to explain this). One day our fridge started to drip. The freezer would cycle through its normal thawing, and all the water would drip down into the fridge and soak up our egg cartons and pool in the vegetable crispers. It was a mess.

We defrosted the freezer we weren’t supposed to ever have to defrost, but the problem persisted. So we called Warren because he fixes things.

Warren came to our house, looked the fridge over. He declared that the freezer’s drain tube was plugged. We thought up a few ideas for cleaning it out, none of which were any good, then Warren asked if we had an air compressor. We did and hauled it in.

Warren plugged it in, let it build up the pressure, and then held the compressor nozzle to the bottom end of the tube. The compressed air went in. The obstruction flew up and out and landed on the counter. The obstruction was a fat fly that had crawled in there, gotten stuck, and died.

We poured a quart of water into that freezer, and it all flowed down into the catch pan at the bottom. Warren fixed our freezer with an air compressor.

Folks, that is creativity.

What did Warren have? He didn’t have passionate hair; I can tell you that. No. He had an objective. He knew basically how fridges worked. And he came up with a couple of options to fix the issue.

Let’s look at another example. Here’s Ed Smylie.

Ed was like Warren. He ran into some problems. Actually, the astronauts in Apollo 13 ran into some problems. Ed was tasked to help solve them. One of those problems was the fact that the astronauts were running out of air.

Ed and the others designed the solution in two days. The ground crew relayed the instructions to the flight crew. The lunar module’s CO2 scrubbers started working again, saving the lives of the three astronauts on board. Of the experience, Ed said that he knew the problem was solvable when it was confirmed that duct tape was on the spacecraft. “I felt like we were home free”, he said. “One thing a Southern boy will never say is: I don’t think duct tape will fix it.”

Ed and his crew saved the day. The made a round peg fit into a square hole. How did he come up with such a creative solution?

Ed had an objective. He knew how the CO2 scrubbers and the shuttle worked. He knew about duct tape. He came up with options.

Let’s look at a few more examples of this. I know you’ve seen some of these.

That is creativity. So is this.

And this . . .

And this . . .

Or this, if you don’t need to go so fast . . .

And this . . .

And this, which is officially called a Bumper Dumper . . .

These fine folks had a goal. They knew the basics of how things worked. They came up with some solutions.

That’s all there is to creativity. Three things. You need to have an idea of what you’re trying to do. You need to have a basic knowledge of how things work. And you have to know how to come up with some solutions to meet your objective.

Not so mystical, is it?

But I can hear some of you complaining. Writing is different. It’s a whole other world. It’s Fiction, which is so significant we must capitalize it. It’s passion. It IS mystical. This is a matter of the heart. It’s not a fridge or space ship or some dumb hotdog roast. You cannot compare these things.

Except I can because they’re the same. It doesn’t matter if you’re trying to invent a different recipe like the folks at Cook’s Illustrated, or decorate your house, or come up with a way to keep the squirrels out of your bird feeders, or make people weep in a movie theater.

What I’ve found is that when we have troubles coming up with ideas, we probably don’t know what our objectives are. Or we probably lack some understanding of how fiction works. Or we don’t know the principles of generating options.

And so we conclude it’s a mystery. It’s arcane lore.

But it just ain’t so. Can you create a redneck toilet? Then you can write a story.

Now, it’s true that a lot of people feel their way through this. They don’t know what they’re doing, but they do it. I did that. Remember: I won an award. But then I couldn’t repeat it. Couldn’t find that groove I’d stumbled into.

I don’t want to stumble around hoping to get lucky. I want to make a living at this. And if I’m going to make a living, I need to produce. Regularly. I can’t be bumbling around, hoping to create something by accident.

The good news is that we don’t have to create by accident. We can create on purpose. There are principles to invention. When we learn them, our productivity will shoot through the roof.

Finding a solution to Apollo 13’s issues might seem impossible to us. But they weren’t impossible to Ed Smylie because Ed had an objective; he knew how things worked up there; and knew how to come up with options.

My intent is that when you finish this series, you’ll know what Ed Smylie knew, except for stories.

For more in this series, see How to Get and Develop Story Ideas