Jennifer Nielsen is the author of Elliot and the Goblin War, the forthcoming Elliot and the Pixie Plot (Sourcebooks, August 2011), and The False Prince (Scholastic, April 2012). She’s also worked for many years with a troubled youth program. I recently sat in on one of her presentations on characters and personality at a writers conference and quickly found myself scribbling down insights. Later I convinced her to share some of that here. Enjoy. You can learn more about her at www.jennielsen.com.

The Rules of Personality

In the Mockingjay series by Suzanne Collins, 16-year-old Katniss Everdeen is selected as one of the contestants for the brutal Hunger Games held by the Capitol each year. Katniss is resourceful, fierce, intelligent, and compassionate. It is these traits she uses in her attempt to survive the Hunger Games. She is joined in the games arena by Peeta Mellark, who is clever, protective, and likable. Like Katniss, Peeta’s traits help him in his fight to survive.

In the Mockingjay series by Suzanne Collins, 16-year-old Katniss Everdeen is selected as one of the contestants for the brutal Hunger Games held by the Capitol each year. Katniss is resourceful, fierce, intelligent, and compassionate. It is these traits she uses in her attempt to survive the Hunger Games. She is joined in the games arena by Peeta Mellark, who is clever, protective, and likable. Like Katniss, Peeta’s traits help him in his fight to survive.

These characters are excellent illustrations of the importance of character in a story. What if Suzanne Collins had not given Katniss her compassion? For those who have read the story, they know changing that single trait would have dramatically changed the plot.

It’s for this reason that character is so important in the creation of a story. If you change the plot, the character will remain the same. But if you change a character, the plot will inevitably change with it.

In order to create a believable human sketch, a visual artist would have to understand the physical body, muscle structure, proportions, etc. In a similar way, for a writer to create a believable character, he must understand the basic rules of personality.

But to create a believable characterization, there are some important things for the writer to understand about personality. Personality is the traits of a person’s core self. For example, there are many different types of people who value and practice honesty (the “trait”). But personality will determine how that trait is exhibited. An extrovert is far more likely to state the blunt truth while an introvert might create an opportunity for the people to discover the truth on their own. So although the trait is the same, there is no single way in which it might be expressed.

In other words, while the presence of a trait is important in developing character, the way it is expressed is equally important. A person’s stubbornness might be demonstrated as passive-aggressiveness or outward defiance. A person’s jealousy might be expressed in withdrawal or by vicious repercussions. It’s personality that determines the way character traits are expressed.

In other words, while the presence of a trait is important in developing character, the way it is expressed is equally important. A person’s stubbornness might be demonstrated as passive-aggressiveness or outward defiance. A person’s jealousy might be expressed in withdrawal or by vicious repercussions. It’s personality that determines the way character traits are expressed.

There are four important things to understand about personality. The better writers understand this, the better they can understand the characters they created.

#1 Personality is Stable. The core of who a person is remains about the same throughout a lifetime. The way a trait is expressed may evolve or adapt as the events of life unfold, but the core self doesn’t change much.

For example, a shy child may hide behind her mother’s legs and refuse to talk. As she grows into adulthood, she will probably learn to manage her shyness and interact in the world. But she will likely never be the outspoken, bold, center stage person.

#2 The Intensity of the Trait Matters. When creating character, most writers stop at listing the presence of a trait. However, that is rarely good enough because it’s really the intensity that matters. Someone who has a hard time forgiving others and holds grudges is probably fairly normal. But increase the intensity of the trait and you may create a villain who’ll go to extreme lengths for revenge.

#3 People Rarely Behave Out of Character. Occasionally, writers finds themselves in a position where in order to make the plot unfold the way they want it to, they must force their character into behaviors outside of anything they’d normally do. This almost always fails the believability test because in real life, people rarely act out of character.

Consider the example of the shy woman. Is it possible that she would willingly get up in front of a crowd and speak with boldness? Of course. But is it likely? No. It’s far more likely that she would find someone else to deliver the message for her, or find another way to communicate the message.

When I’m speaking about this issue to groups, a common response from writers who are facing writer’s block is that this is the root of their problem. They are trying to force a character into a behavior not consistent with their personality. The entire scene becomes forced as the character literally balks at the writer’s attempts.

#4 People Tend to Rework the Same Issues Throughout Life. Everyone has “issues.” Some are more major than others, of course, but we all have them. And whatever it is that we battle, we likely battle it throughout life, even if the way we experience that issue evolves.

For example, the teenager who becomes explosively angry is later the man who may take out his anger on his wife or children. In later life that trait may evolve so that he turns his anger inward and develops a drinking problem. Or perhaps the man matures and mellows. Perhaps he’s learned to manage it, or perhaps he’s too tired to create the same fuss as when he was younger.

In April 2012, I’ll release a series with Scholastic that begins with Book 1: The False Prince. The protagonist in this story is a defiant boy named Sage who must use his own cleverness, determination, and strength to survive a contest that will name the winner as the false heir to the throne.

As the writer of this series, it was important for me to understand Sage’s personality if I was going to create a believable character. One of his core traits is his instinct to rebel. It’s a more intense than would generally be found in his peers, so I needed to respect the fact that he would rarely back down from a fight, regardless of the consequences. There is one scene in the book where Sage steals an item from his master that Sage believes was stolen from him. He refuses to tell anyone where he hid it, even though he knows the consequences will be serious. I didn’t want those consequences to happen to Sage, but he would not have had things any other way. To attempt to create a story where he gave in to the master would have cheated the character, the story, and the reader.

Likewise, writers must understand that creating great characters begins with understanding the rules of personality. And when it’s done right, whether it’s Katniss Everdeen, or any of your favorite characters, the reader will always remember them.

*

JOHN SEZ: I particularly like #2 because homo-ficti need to be a little bit larger than life. A litter more courageous. A little more finicky. A little more skilled. A little more outrageous. Exaggeration is one of the key tools for developing characters.

The statements about the core part of personality being stable and long-lasting, and folks dealing with issues for a long time, are interesting to me as well. It seems like this is where deep motives lie.

Of course, I know I don’t start with personality grids when developing characters. But I do eventually try to peg my characters. I’ve found that having a dominant impression, a type, helps a great deal when working with them, even if my characters mix or bend the types. If I know that this one is a wise-cracking farmer, that one a quick-tempered tailor, and that one a no-nonsense baker, it makes them easier to work with. It makes it easier to envision how they might react in a given situation.

In fact, I think I’ve created my most enjoyable characters when I didn’t try to make them super complex. They might have had things that occured in their past that affected them greatly. They might be dealing with terrible dilemmas now. They might have a number of interesting details about them. But if I can peg them in my mind as this or that type of person, it seems the scenes flow more easily. I can improvise the dialogue and their reactions much better in my mind as I write.

Sometimes I can capture that type with a description, e.g. “scary smart farmer.” Sometimes it’s enough to get a voice or a photograph or link them to someone I know. Sometimes I’ve linked them to animals and that gave me the center. Very often they form as I write them. They often have to come on stage first and have me start writing them for everything to coalesce.

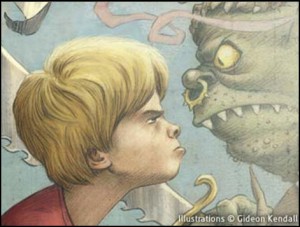

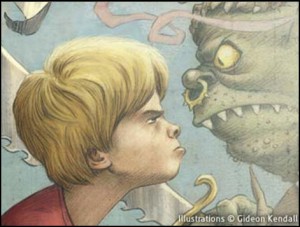

Check out Nielsen’s site. I love the first line of Goblin War. I mean not only does she get all these fab illustrations for her book, but then she opens it with this: “When he was 8 years old, Elliot Penster started an inter-species war. Don’t blame him. As anyone who has ever started an inter-species war will tell you, it’s not that difficult to do.” Elliot is trick-or-treating at the moment, everyone thinking he is dressed up as a hobo, when in reality he’s just wearning his normal day clothes. Hum. A little homo-fictus anyone?