You can read the transcript of my remarks at the American Librarian Association (ALA) conference in Chicago on July 11 below as well as the supporting information.

IS SF/Fantasy Key to Teen Literacy?

Intro

I am so happy to be here. And I’m happy share some good news. David McCollough, the Pulitzer prize winning historian shared this fact in his commencement speech at the University of Utah this spring. “There are yet “more public libraries in America than there are McDonalds.” [Cheering]

We have not yet been assimilated!

Of course, this is due in a large part to you, the librarians who care for the collections and take care of the patrons. Which is why I think you deserve a big round of applause. Give yourselves a hand. [Applause]

Fiction is a literal drug

I want to start my remarks with two quotes.

Ray Bradbury was recently interviewed in a NY Times article He said, “I don’t believe in colleges and universities.” This is what he said, “I don’t believe in colleges and universities. I believe in libraries.” He said this because when he graduated from High School he didn’t have enough money to go to college. So he went to the library three days a week for ten years.

The next quote is from the great poet Dylan Thomas–“Do not go gentle into that good night, rage, rage against the dying of the light”–that guy. He said, “My education was the liberty I had to read indiscriminately and all the time, with my eyes hanging out.”

If you look at Bradbury and Thomas, they read, not because there was some grade involved, not because someone went after them with a stick—they read from hunger. From thirst. They read with wild abandon because they found in reading something they couldn’t find elsewhere.

I want to suggest one thing they found was a drug. [Laughter] I’m not speaking in metaphor. I’m talking about real physical response. As real and physical as the response you get when you or I take aspirin, brandy, or crack. Well, I hope we’re not taking crack. [Laughter]

When we think about drugs we think about pills, smoke, injections. But those are simply one set of delivery mechanisms for chemicals that trigger a physical response. There are other delivery mechanisms. Other triggers. One of them is fiction.

Now I don’t have time today to detail how this works. But I will write it up on my website for those who are interested. The key thing to remember is that fiction, the kind of fiction we love, the kind that keeps us up at night sitting on the edge of the tub or locked in a closet with a light, the kind of fiction goes beyond cognition, beyond data and facts. We find it so pleasurable precisely because it triggers and guides a physical response.

So how does all of this apply to science fiction and fantasy? Here’s the deal. And here’s where we come to our topic. Science fiction and fantasy is, for our youth, one of the most powerful gateways drugs into the fictive experience. Of course, there are ideas in science fiction and fantasy that ripple out to the society. But even if there weren’t, the happy side-effect of an addiction to this drug is improved literacy. And we all know how much that impacts.

Numbas

Now I know those of you who work with young adult circulation have seen this. But I thought it might be interesting to get some actual numbers so we can start to gauge the scope of the science fiction and fantasy effect.

My interest in this began when I saw the results of the latest NEA survey. They have this graph showing reading rates in all age groups dropping horribly since 1982. By 2002 the graph is taking a nose dive. Then in 2008 everything turns around. And among the young adults (18-24), we see the biggest increase—9%.

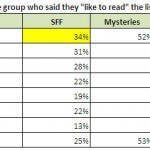

I saw they had a genre preference question in this survey. Of course, I wondered about science fiction and fantasy. So I contacted the NEA and dug into the details. It appears that 34% of the 18-24 group say they like to read science fiction and fantasy. That’s a big number. That’s 1 in 3.

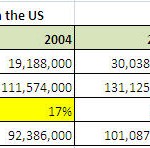

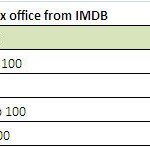

Of course, I wanted another data pont, so I went to BookScan and asked for data on book sales. Because the wonderful people there love librarians and Tor Books, they said of course. We looked at juvenile fiction sales from 2004-2008. What we saw was that science fiction and fantasy grew 144% during that period. All the other genres only grew 23%. We also saw that science fiction and fantasy currently make up almost 30% of the juvenile fiction market. So about 1/3.

Now there are some problems with the BookScan data. Yes, it only cover 60-70% of the market. It’s not in Wal-mart, grocery stories, and a few other places. But what’s more problematic for this issue is that they don’t break up the juvenile sales by age. It includes everything for folks one month old to age eighteen. So I’ve got books like Go Dog, Go in the dataset along with Twilight and Go Dog, Go isn’t categorized as fantasy. [Laughter] My suspicion is that if we narrow it down to the middle grade and YA group, we’ll see more science fiction and fantasy.

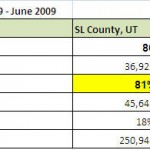

So I needed someone who did break it up by age. Well, who does that? You do. Libraries do. Besides, a lot of youth don’t have the $ to buy lots of books. So I went to some libraries in Utah and Ohio and got their YA fiction circulation stats. Here’s what I found: 60-80% of the YA fiction circulation is science fiction and fantasy. This does not include graphic novels or magna. It’s text fiction.

Folks, this is a big drug. I don’t know what part science fiction and fantasy played in the rise in reading rates, that would require a larger and more rigorous study. But I can tell you this: We want to see the impact of science fiction and fantasy on our society? We’re seeing it right now.

My Story

This large effect makes sense because science fiction and fantasy deliver experiences that are intersting to and matter to youth. It’s chock full of and encounter with the strange, weird, and wonderful; adventure and danger; doing something meaningful; being someone special, someone desireable, someone wanted in the group. All that coming of age stuff. So no wonder it’s a huge gateway drug.

I know that it was in my case. I wasn’t a reader. I don’t think I read more than twenty or twenty-four book from kindergater to sixth grade. I look at the little fellows in my local school today and they read that many titles in the first six months of the first grade. But I didn’t. I wasn’t a reader. I do remember loving the look and feel of these small chubby books. [Laughter]

I would take them them up to the librarian to check them out. She’d look down at me. “Are you going to read all that?” she’d ask. “Yes,” I’d say. Of course, it was lie. [Laughter] It was a huge lie because I would take them home and put them up on my dresser and just look at them. Just loving the look and feel. And then when it was time to check them in, I’d take them back and give them to the librarian. “Did you read all that?”

“Yes,” I’d say. And that’s how I became an author–lying to librarians. [Laughter]

Now in sixth grade my sister, we were in the car, I had four sisters and we had one TV, and so you had to reserve the time for your programs. So my sister says, “I have to watch The Hobbit for school.” Now I don’t know anything about The Hobbit. It sounded like a romance. [Laughter] I protested. No, way–we’re not going to watch some dumb kissing thing.

“No,” she said. “It’s got dragons.”

“You’re lying,” I said.

I was convinced I was doomed. But it didn’t matter. We watched it. It had dragons. And I loved the experience so much I wanted another hit. Shortly thereafter my mother and father went on a business trip. I went over to my buddy’s house. So the first day we come up out of the basement to go to school and I said, “Oh, I’m feeling sick.” So my buddy went off to school and I went back down into the basement and played hookie for two days and read The Hobbit.

It was amazing. More amazing than the movie. I had to have that experience again. And so I read Ursula LeGuin, Patricia McKillip, Donaldson, Terry Brooks. I kept reading because it delivered a cognitive-physical experience I loved. Of course, I didn’t put it that way back then. It was more along the lines of, duuuude. [Laughter]

Now I got a BA in English and a Masters in Accounting. Those degress required a lot of reading. But I didn’t develop the requisite literacy skills in school. I developed them in science fiction and fantasy.

And so when I started to write I was naturally drawn to fantasy. Having experienced this wonderful thing, I wanted to produce that and share it with others. So this novel that’s coming out has the gosh-wow I still love. It’s set in a world were humans are ranched by beings of immense power. There’s a young man and young woman in terrible trouble. So it has monsters, magic, and mayhem. But I also found fantasy big enough to let me explore other things that have become more important to me as I’ve aged. Like family, sacrifice, and redemption. And I hope people enjoy all that. But ultimately, I hope this book does for someone else what The Hobbit did for me and opens a door to a wonderful addiction. And, of course, as a powerful side-effect, improves the literacy of some rascal or rascaless. [Laughter]

Conclusion

I want to end where we began with that Thomas quote.

“My education was the liberty I had to read indiscriminately and all the time, with my eyes hanging out.”

That kind of wild abandon will happen when the drug takes effect. And for many of our youth, probably at least one in three, that’s going to be when they ingest a few ounces of SF & Fantasy.

Thank you.

[Applause]

Supporting Numbers

How fiction is a drug

Emotion is not a cognition, although cognition plays a part. It’s not just in your brain. It involves a physical response, which means it involves chemicals.

We sometimes forget that our bodies produce a staggering number of chemicals. Sometimes they produce in response to external stimuli—the sun triggers the creation of vitamin D, ingested sugar triggers the production of insulin, the sight of a ravening lion standing not five feet away with nothing between him and me produces, among other things, adrenaline.

Lots of these reactions, we don’t notice. But there’s a whole group of these physical responses that we do. We lump them together and call them emotions.

Jenefer Robinson in her wonderful book Deeper Than Reason, explains, “Emotions are our way of responding to events in the environment (either external or internal)” that matter to us. They are “physiological changes that register the event in a bodily way and get us ready to respond appropriately.” Fight, flight, pursue, woo, investigate. They focus our attention, get us ready to take action, and communicate all this to others.

So while I might not feel the production of vitamin D, I do feel the fear of the lion. Fear is a wonderful thing—it keeps us alive. It raises our heart rate, pumps us full of drugs that prepare us to flee or fight. The emotion writes itself on our faces in order to, among other things, communicate the situation to those around us, warning others and calling for help. It is a physical response. Yes, there are cognitions involved, but there are also chemicals.

The latest research on emotion shows that emotion is a process that involves three things. (1) An affective appraisal of our environment that signals something important to us—a threat or opportunity. (2) This triggers an immediate physical response (chemicals, galvanic skin response, accelerated heart rates, facial expressions, etc.). (3) At this point cognitive (conscious thought) appraisals kick in and help us monitor the situation and moderate the physical response.

For example, I go out to the yard and step on this thing that slithers through the grass. The sensory signals immediately trigger a physical response to get me ready to flee or fight–heart rate, adrenaline, etc. Then I notice the snake is far too long. I look closer. It’s the garden hose. My physical response changes. I laugh, feel relief. Research has shown that when we read text, the same process occurs. We do indeed have the same types of physical responses. In some cases they’re more intense.

Now here’s the thing. This physical response is triggered not just by threats and opportunities we perceive with our senses, things out there. It is also triggered by thought. Thoughts deliver a physical response just as surely as crack does. We have the research to prove it. In fact, sometimes thought delivers a more powerful physical response. Here’s but one example. Did you know that people with a phobia of snakes have a stronger reaction to reading a passage about snakes than they do to the actual critter?

This is where fiction comes in. As I stated in my speech, fiction, the kind of fiction we love, the kind that keeps us up at night sitting on the edge of the tub or locked in a closet with a light, the kind that lingers in the fabric of our clothes and our hair long after we close the book, that kind of fiction goes beyond cognition, beyond data and facts. That kind of fiction triggers a physical response.

It does this, and this is one difference from emotion triggered by our own thoughts or the sensory data we pick up from the world, because fiction, by its very nature, its very structure, is actually guiding our emotional response. Our physical response. This management of the response is in fact one of the things that we find so pleasurable about it.

To find out more, please read:

- The Science of Emotion by Randolph R. Cornelius

- Deeper Than Reason: Emotion and its Role in Literature, Music, and Art by Jenefer Robinson

You may then want to search out texts by Dolf Zillmann, Jennings Bryant, and Peter Vorderer.