In part one, we talked about the story problem and its central role in reader suspense. We also talked about a man scratching his bum.

In part two, we discussed the three character factors that are critical for reader suspsense and how they also help make a character rock.

(For those of you just starting the series, you can find links to the other parts in the On Writing area of the site.)

So let’s say you’ve already got all that. You’ve developed a character who is sympathetic and interesting, maybe tugs on the reader’s sense of wish-fulfillment. You’ve given that character a problem that’s significant enough for readers to be intrigued. Now what?

Let’s go back to the objective. Readers want to hope and fear for a character; they want their tension to build to a pitch. Then they want to have a cathartic release.

Character and problem by themselves don’t go anywhere. You still have to build reader tension to a sharp point. So how do you do that?

You do it with plot.

Plot is nothing more than the character’s attempts to solve the problem and the results of those attempts. There’s no mystery to it. A character has a problem. Character tries to solve the problem. And something happens as a result.

The key is to remember that the plot has a job to do. You can’t have your characters go about solving the problem in any old way. You can’t have just any old results. Form follows function. To deliver what readers want, you have to develop the plot in a manner that builds the reader’s tension. If the story’s about a happiness problem, all of the attempts and results should increase the reader’s hope or fear for the character. If it’s a mystery problem, the attempts and results should increase the reader’s curiosity.

In this post, I’m going to discuss the Pareto factors for doing this. And these factors all revolve around making the problem hard to solve.

Clarity

The first part of making problems hard to solve has to do with clarity.

(Blink)

Wait a minute. Clarity? Um, what? How exactly does that make a problem hard to solve?

Clarity doesn’t make problems harder to solve. What is does is provide the critical function of allowing the problem to exist in the reader’s mind in the first place. The simple truth is that readers cannot hope and fear for anything if they don’t understand what’s going on.

So the very first thing you do is make sure the reader knows or suspects what’s at stake, i.e. what’s to be gained or lost. They need to understand something of the danger/threat, lack/opportunity, or mystery. They also need to know or suspect why it’s going to be difficult to solve the problem or take advantage of the opportunity. This means the reader will need to know about or suspect possible obstacles and conflicts the character may have to face.

This doesn’t mean you have to reveal all. It just means there must be something to fear and hope for.

When you don’t explain the danger or opportunity or mystery, then the most the reader can feel is confusion, maybe brief moments of surprise. Imagine a thriller that fails to establish that Bob kidnapped George’s wife who is a Chinese spy. George and Bob run around for 100 pages and the whole time the reader is thinking: “When’s the story going to start? What’s going on? Why is George chasing Bob?”

The classic example of this is given by Alfred Hitchcock in an interview conducted by Francois Truffaut. Here’s Hitchcock.

There is a distinct difference between ‘suspense’ and ‘surprise’, and yet many pictures continually confuse the two. I’ll explain what I mean.

We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let us suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, ‘Boom!’ There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but prior to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table, and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware that the bomb is going to explode at one o’clock and there is a clock in the décor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions this same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene.

The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: ‘You shouldn’t be talking about such trivial matters. There’s a bomb underneath you and it’s about to explode!’

In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second case we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense. The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed. Except when the surprise is a twist, that is, when the unexpected ending is, in itself, the highlight of the story. (François Truffaut, Hitchcock, pp 79-80)

Hitchcock gives two more great examples in his essay “The Enjoyment of Fear,” first published in Good Housekeeping in 1949. (I think there’s some zing in the juxtaposition of housekeeping and the enjoyment of fear, don’t you think? Magazines were so different back then.)

Readers feel surprise when something unexpected occurs. By definition, they do not see it coming, even if it makes sense after the fact. So to create this effect you need to withhold information and lead the reader to have different expectations. Then wham!

Readers feel curiosity when they’re given enough information to form a question but not the answer. For example, in a murder mystery, we know someone’s been killed, but who did it? And why? In another story, like McDevitt’s Ancient Shores, the character finds an odd thing in the ground at his farm. When he digs it up, he finds a modern-looking boat made of a material more refined than any known to man. We know what he found, but what is this and how did it get into his field? With other stories where characters face dangers and lacks, readers feel curiosity about what might happen next.

However, if we want our readers to hope and fear for a character, we have to give readers more information. We have to let them know what’s at risk—what’s to be lost or gained. We have to let them know what the obstacles and conflicts are, what MIGHT happen. After all, how can you fear for a character if it’s smooth sailing to the finish line?

No information = no possibilities in the reader’s mind = no expectations = no suspense.

This isn’t to say we must eschew surprise and curiosity. Both are delicious. In fact, both actually help create suspense. So the point isn’t to avoid them. The point is to make sure we understand that we cannot create suspense by withholding the situation. We create it by giving the reader all the information we can without giving away all the details of the resolution or key plot turns until the moment they occur.

BTW, I say “all the details” because sometimes, despite our best attempts, the reader will see some of the plot turns coming. But if we’ve done it right (fingers crossed), on those occasions they will only see a part, and the part they don’t see will pack enough surprise or particularity to delight.

Make the Problem Hard to Solve

So readers want to hope and fear for a character. To feel this, they must not know what WILL happen, but do need to suspect or know what MIGHT happen and feel tension about the possibilities. They want that tension to build, and then they want to feel a cathartic release.

The reader will continue to feel that tension as long as the problem is unresolved (the danger remains, the character continues to suffer hardship, the mystery becomes more puzzling) AND the situation changes in such a way that the reader’s worry grows.

How do we make sure the problem persists and intensifies for forty to seventy scenes (an average range for many novels) despite the character’s efforts?

We do this by throwing OBSTACLES into our character’s path. We make the problem hard to solve.

I’ve listed the types of things that do this below. But remember: these aren’t ingredients to a recipe; they’re options. You don’t need to think up something for every category. You just need enough to bring the problem to life.

1. Put the Character at a Disadvantage

The first way we make the problem hard to solve is by putting the character at a disadvantage. The disadvantage may be a small, medium, or large, depending on your taste and the kind of story you’re telling. There isn’t one type or level that’s best for all objectives. But our characters do have to have some disadvantage; otherwise, there’s no reason for readers to fear for them.

Lack of knowledge

One of the most common disadvantages is a character starting off not knowing how to solve the problem. Or not having a critical piece of information that will allow them to solve it.

For example, think of all the murder mysteries you’ve read or seen. The character starts off not knowing who the killer is or why they did it. In the movie Taken, the father doesn’t know who stolen his daughter or where they’d taken her. He had all the skills and power to resolve the issue once he found her, but he lacked vital bits of information.

Sometimes the characters think they know what the problem is, but when they try to solve it, they realize they didn’t really know what the problem was. It’s called misdiagnosis.

For example, in The Incredibles, Bob goes to the island thinking his problem is a rogue robot. But his real problem is Syndrome.

In another story, a man might think his problem is that his wife is stepping out on him. When he tries to resolve that, he learns she’s actually being blackmailed.

In Dean Koontz’s The Husband, a gardener starts off thinking he’s being threatened by people who want to get to his brother’s money. He tries to solve that problem only to realize that it’s a plot by his brother to kill him.

Anytime your character doesn’t how to solve the problem or doesn’t know the exact nature of the problem, it makes the problem harder to solve.

Lack of skills or power

You can make a problem harder by limiting the character’s skill or power in some way.

Luke Skywalker knows the death star is going to blow the world the rebel base is on into smithereens. We have no question about what’s going on. Luke knows what he needs to do—start a chain reaction that will blow the thing up. What Luke lacks is the power to easily go in and execute the plan. He doesn’t have his own death ray. Doesn’t have computers that can target with precision. All he’s got are dinky little X-wing fighters. He’s limited in his ability.

A Jewish woman is taken by the Nazis. Her lover, who is a Nazi soldier, wants to rescue her. But the lover has no power to order the men to release her. He has no money to pay them off. This doesn’t mean he can’t rescue her. But it does mean he’s going to have to find some other way. It means resolving the issue is going to become much harder.

Personality flaws

Sometimes personality flaws can put the hero at a disadvantage.

Maybe the hero is recovering from an addiction to some drug and finds himself being required to snort a line in front of the villain to prove he’s legit. Maybe he’s a bigot and won’t accept the help of a woman, but she’s the only one with the key. Maybe he’s too proud to admit he’s wrong. Maybe he’s a slob and loses things, including the key to the getaway car. Maybe he doesn’t know when to stop drinking. Maybe his lack of self-control leads him to follow after a woman who comes on to him and then leads him right into the hands of the villain. Maybe he lacks social graces, but needs some high class to infiltrate the villain’s circles. Maybe the character has an issue with trust, has been burned too many times, and begins to suspect the other team members.

Maybe the character’s virtue is the source of his flaw. He’s so willing to see the good in people he blinds himself to who the villain really is. She’s so committed to doing her duty that she’s sacrificing her relationship with her husband and children for it.

Of course, flaws affect our sense of deservingness. Take personality flaws too far and our hero will become annoying or despicable. At that point, the reader stops rooting and worrying for them. Still, they can be a rich mine for making the problem harder to solve.

Handicaps

If all a character needs to do is snap his fingers to solve the problem, then readers can’t worry for him. Unless, of course, he’s missing fingers. Any handicap will put our characters at a disadvantage.

Sometimes the handicap is physical. In Seabiscuit, the jokey is blind in one eye. This makes it very difficult during a race to see when someone is riding up on his blind side. It also makes it hard for him to see openings ahead. It puts him at a disadvantage in a race. In the movie Wait Until Dark, three criminals threaten a woman who is blind. In Gattica, the hero has DNA that makes him weaker than the others wanting to travel into space.

In other stories, the handicaps might be emotional, mental, or social. In Forrest Gump, the hero is mentally handicapped. In other stories, heroes are tormented by fears of snakes, spiders, being alone.

Handicaps can be interesting all by themselves, but when they become a disadvantage to the hero’s goal of solving the problem, they affect suspense.

Time limits

Another disadvantage is having a time limit. Of course, a time limit of a gazillion years doesn’t make most problems harder to solve. Time limits put our hero at a disadvantage when they don’t allow any wiggle room or when they simply don’t allow enough time to solve the problem by normal means.

Next time you read a book or watch a movie, notice how many deadlines, ticking clocks, and time bombs are used.

We Want Underdogs!

In the end, the disadvantages our characters have are only useful if they make the character the underdog when compared to the opposition.

Our hero can have all sorts of great qualities, but the opposition must have something that gives them the advantage–more money, more power, more knowledge, more connections, more training, more whatever is important in the story. This doesn’t have to be huge. Sometimes the hero is the underdog simply because he starts two or three steps behind the villain. The first part of many stories features the hero just trying to catch up.

For example, In Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones has mad skillz and knowledge, but he’s outnumbered, outgunned, and outfinanced. And the Nazi’s always seem to beat him to the punch. In Dean Koontz’s The Good Guy, the hero has great skills, but it’s just him against the US government. In The Lord of the Rings, we’ve got a wizard who can work wonders and an elf that can see and hear for miles. But Sauron has so much more. By the end, all we are left with are two little guys and a smelly freak job.

The worse the obstacles and odds the characters face, the more tension and, therefore, relief the readers feel. Think about this. When do you cheer more? When your non-ranked, underdog sports team beats the number one team in the nation, or when they slaughter the local pee-wees?

2. Add Conflicts

The second way to make problems harder to solve is to introduce people and things that actively work against or resist our character. Your characters can come into conflict with others, the setting, and themselves.

Conflict with the opposition

You will have points of conflict with the opposition. That’s a given. The smarter and more powerful the opposition, the harder the problem is to solve, the more the reader can worry, and the bigger the triumph at the end. So you want to make your opposition character and team a real threat.

The best way I’ve found to do this is to play the story as one-man chess, thinking not just about the hero, but about the opposition as well. The hero is, for the opposition, a problem. And so I’ve found it very productive to develop the opposition’s goal, motives, and plan. Then as the story progresses I stop and think: what cunning/smart/scary reactions might this opposition character have to what the hero just did?

Remember, the better the opposition, the more tension the reader will feel. And the key to the opposition, villain or decent chap, is the goals, motives, and plans.

Conflict with the other good guys

Sometimes we think only about the opposition, but the other good guys can provide so many delicious conflicts. In fact, if you think about casting variety, this is just an extension of that topic.

So maybe the hero is about to break a moral code some of the other good guys won’t, or vice versa.

Maybe some of them just can’t stand the risk.

Maybe one of the good guys has lost the vision and turned traitor, as Cypher did in The Matrix.

Maybe the good guys have different reasons for being on the team. One guy joins the army because the judge told him he could join the army or join the convicts in the big house. Another guy joins because he feels a duty and all of the men in his family have served since the Civil War. Maybe another guy joined because he felt like this was the only way to prove to himself he wasn’t a coward.

Maybe the hero is teamed with someone that is a complete opposite. The hero’s a neat freak, the partner is a slob. The hero is highly-educated, but his right hand man barely got his GED. Maybe one of the team members is a KKK sympathizer, and another one is black.

As with the opposition, the key here is taking a moment to explore the other characters’ goals, motives, and plans.

Conflict with bit characters

After looking at the main characters in the story who have goals and plans that conflict with the hero’s, you might want to see if there are any bit characters who do the same.

Maybe the hero drives into some bad neighborhood to try to get some information from someone. When she comes out from her meeting, she finds her car stolen.

Maybe in one scene the bad guys start shooting at a playground. The hero rushes them, but a mother who is trying to get her son off the swing gets in his way.

Maybe the hero needs information, but the guy working security has a mortgage in default and can’t lose his job.

Maybe our hero is trying to get away and an vigilante truck driver hears the chatter over the police channel.

Think about the other people that might in the scenes and what conflicts they might pose. If one is too delicious not to use it, put it in.

Conflict with the setting

The setting includes everything that’s not a character with some part—geography, technology, culture, religion, government, etc.

Maybe the hero wants to stop the two men carrying his little boy off, but there’s a raging river between him and them.

Maybe the hero wants to get back to camp, but the temperature drops and drops and drops as in Jack London’s “To Build A Fire.”

Maybe the hero encounter asteroids, trains that are late, horses that are high-spirited, and insects carrying malaria.

Maybe a hurricane is coming in and making it rough for our brave gal to go out to sea to save her husband whose boat is swamped.

Look around in your setting and see what things might provide obstacles to your character.

Conflict with self

The last, and sometimes the most powerful, type of conflict is a character’s conflict with herself or himself. This type of conflict arises when a character wants two things that seem to be mutually exclusive.

For example, maybe the hero wants to marry the girl of his dreams.

“I love you, Luke”

“But you’re my sister, Leia.”

He wants that intimate relationship; we as the audience want it for him, but we also want him to avoid the freak zone. We can’t do both. Unless . . .

“But,” Leia says, “I take birth control.”

(Zoiks! Run, Luke, run!)

Maybe, like Katniss in Hunger Games, the heroine wants to live, but in order to do that she has to kill a boy who has been nothing but kind to her family. She wants to survive and be kind. She can’t do both.

Maybe like John Proctor in The Crucible the hero can keep his honor only if he dies. He wants his honor. He wants his life. He can’t have both.

Maybe like Bob in The Incredibles, the hero wants to escape a life of drudgery, but he also wants to keep his family safe. Alas, it seems he can’t have both.

Have you noticed how many love stories pit someone’s desire for independence against his or her desire for love? It’s simply hard to solve a problem when doing so means you must give up something else of great worth.

When developing your story, take some time to explore potential conflicts inside the main character. You don’t have to include these types of conflicts in every story, but when you come up with a good one, it’s such a lovely way to put your hero and readers through the wringer.

3. Make Progress with Continuing & Growing Troubles

The third way to make a problem harder to solve is by making it grow despite or because of the characters actions.

But that doesn’t sound like progress–how do you make progress if the character’s troubles not only continue but grow? Simple, the progress I’m talking about is in sharpening the reader’s tension. As the plot complicates, the reader’s tension grows.

Think about the flip side of this. The moment you solve all the problems in the story, the story is over because the readers have nothing more to worry about. So you must continue to give them troubles.

This doesn’t mean the characters can’t solve small parts of the problem along the way. It doesn’t mean good things can’t happen to the character. After all, we want to fear AND hope for the characters.

So, for example, in the middle of Hunger Games, we get two nice chapters where things are looking up for Katniss. Of course, we don’t want to think about the fact that she’s going to have to eventually kill the person she’s teamed up with. Or the fact that the careers are out there killing off everyone else, narrowing down the contestants until there’s nobody else but Katniss to hunt. So Katniss still has problems, but for a few chapters we get a break from the tension. And then we’re plunged back in, worse than before.

What this does mean is that despite the successes, our character still fails to solve the problem and, very often, makes it worse.

So as our character attempts to solve the problem, she will experience disasters, calamities, setbacks, misfortunes, upsets, betrayals, unforeseen obstacles, desertions, and failures. Plans will go awry. The villain will counter with shocking blows. The character will learn things that twist her (and the reader’s) understanding of the problem in more dangerous directions. The problem will become more intense (see part 1), more immediate, probable, significant, and specific. More in the character’s life will be put at risk.

Maybe the character starts the story being personally threatened by the villain, but as the story progresses the villain begins to threaten his children. Maybe our inexperienced team sets out and halfway through the story, their leader (Gandalf or Obi-wan Kenobi), the guy who was keeping them all from dying, is killed. Maybe our airplane gets shot and the fuel leaks out, and our perfect escape crashes into the mountains only miles from where we began.

All of these plot turns keep the tension building.

Another thing they do is keep the story from becoming monotonous. A fight where the positions of the hero and the opposition remain static quickly begins to bore. Think of a football game where the score remains at 0-0 for three and half quarters. Both sides keep getting the ball and keep having to punt after three downs. Nobody gets injured. Nobody makes any yardage. Nothing changes.

Boring.

So we keep the plot turning, keep adding complications and revelations and conflicts and surprises. We keep giving the reader something new to increase their hopes or fears.

4. Avoid Predictability with Surprise

The last way we make the problem hard to solve is by making sure nothing works as planned.

Readers will have a hard time hoping and fearing if they can predict what will happen. When they pull back and cogitate, they may suspect in the end that the hero will win. But if we’re telling the story effectively, they won’t be pulling back much. They’ll be focused, the details of the immediate events filling up the capacity of their working memory. They’ll be living in the moment on the page and worrying about the characters. And the surprises we deliver will put them off balance. They’ll make it so the reader can’t predict exactly what will happen next.

Remember: reader’s don’t want to know what WILL happen. They want to know what MIGHT happen and feel tension about the possibilities.

So some surprises will convince the reader that our hero MIGHT indeed lose. The hero’s smart and bold plan, which everyone expects to work, fails. The one sidekick we thought we could count on turns traitor. The opposition tricks our hero into a setup that now has the cops thinking he committed the crime.

Other surprises will give the reader reason to think they still MIGHT win. Our hero gets a critical clue that leads her one step closer to the killer. Maybe she beats up the villain’s henchman and escapes. Maybe the sidekick who rejected her at first decides to come help after all. Of course, we can’t give our hero an easy go of it. We still need them to fear. But our characters always have to have a chance, even if it’s tiny.

We evoke surprise in the reader when we lead them to expect one thing and deliver something else. Sometimes you do that by structuring the story so the lead character, and the reader, don’t have all the facts up front. And the current set of facts lead to one conclusion. Sometimes you skillfully plant ideas into the reader’s mind that misdirect their expectations. A classic example of this is the red herring in mysteries.

However you do it, surprises need to be believable to work. They need to be logical. Readers will not hope or fear if the opportunity or threat is hokey or forced. Rubber snakes only scare people when they’re mistaken for the real thing. So give the audience surprises that take their breath away, and watch their tension and delight rise.

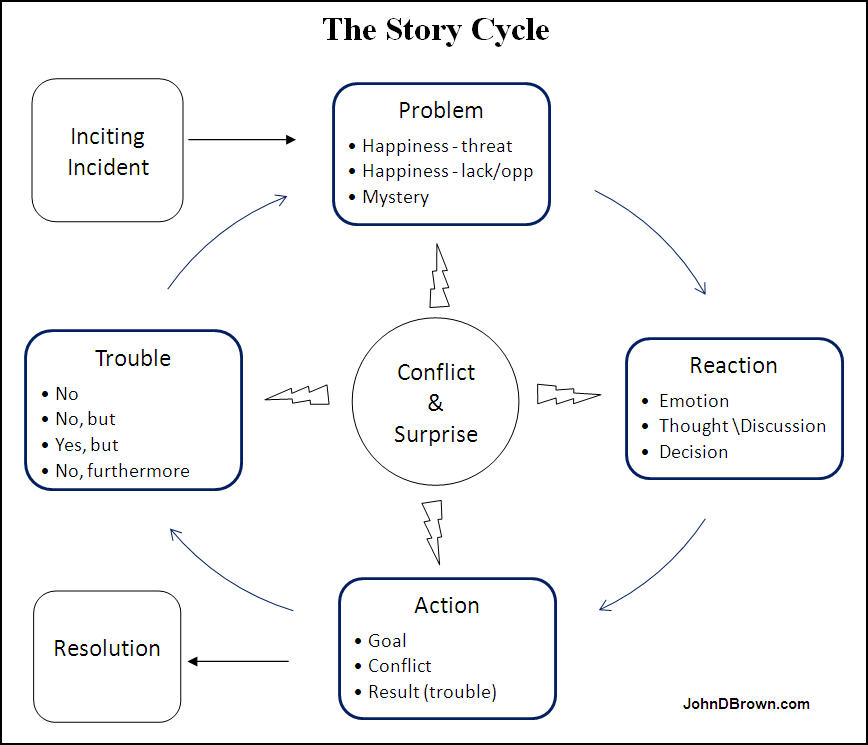

Putting It Together with The Story Cycle

It’s good to know you need to make the problem hard to solve, but how do you use all the obstacles to develop the plot? How do you layer them in? How do you start and move forward?

You follow the story cycle, which is simply a model of how we humans go about solving problems, and apply the techniques listed above in ways that make sense to you and spark your interest. You can move forwards or backwards, whatever is most productive to you at the time.

I’ve inserted a diagram of the cycle below and will explain each element. Please note that this is built on the wonderful discussions of scene and sequel found in Dwight Swain’s Techniques of the Selling Writer and Jack Bickham’s Writing and Selling Your Novel and Scene & Structure. I’ve added my own insights, but if you want an expanded discussion of this topic, you might want to read what they have to say there.

One thing to note before we dive in is that the parts of the cycle don’t always correspond to individual scenes on the page. You can present an action or reaction in a scene, a sequence of scenes, narrative summary, or, if it’s insignificant, you might not present it at all. The decision about what to put into scene, narrative summary, or leave out entirely is something I’ll discuss in the part of this series that focuses on scenes. For right now just know that story is about a character’s attempts to solve a problem and the results of those attempts and you’ll be sharing only those parts that make a difference.

Inciting Incident

Everything starts at the point when the problem arises. In fiction, we call this the inciting incident. In real life, it’s the “ah, crap” or “oh, no!” moment. Or, if this is a story about a lack/opportunity, it’s the moment of “dude!” and “oh-my-gosh, oh-my-gosh!”

So with a murder mystery, it’s the point in time when the lead character learns about the murder. In a story about a kidnapping, it’s the moment when grandma is shoved into the back of the van. In a love story, it’s the moment when the girl meets the boy.

The inciting incident thrusts the lead character and the central problem together. The central problem is the main problem the character will be dealing with throughout the rest of the story. Maybe Lead took action and found the problem. Maybe Lead was just minding her own business and the problem found her. It doesn’t matter.

There may be other subplots in the story. There will be changes, complications, and developments in the central problem as we go along. We don’t need to know everything about the problem in the beginning. We just need to know that the character has a problem and that this problem is going to be the one the story is about.

Reaction

So what do we do in normal life when presented with a problem? Let’s say water starts dripping out of the light fixture right above your kitchen table. Maybe the wiring starts to spark. What do you do?

First, you will experience some emotional response. It might be alarm (Oh, crap! That might start a fire!), or anger (Those morons who rent upstairs!).

Next, you consider your options. Maybe you need a towel or bucket under the fixture. Maybe you should go bang on the door of the apartment above. But maybe the people are gone, so you’ll have to break in a window or try to force the door, or call the apartment manager. Maybe you call your buddy who is in construction. Depending on the problem, you might find yourself in a discussion, performing some analysis or research, or sketching out a plan.

At some point, you decide on a course of action.

When we face any problem in real life, we follow that same sequence of:

- Emotion

- Thought

- Decision

For our plot to feel real, we need to follow that sequence with our characters as well.

Sometimes in real life we move through the reaction process quickly. Sometimes it takes a while. This happens in a story as well. But because you want to make things clear, you’ll remember that any non-standard decision will need an explanation. So you’ll put that into the thought part so it makes sense to the reader.

Please note as well that reaction is the place where we have the most time to explore motive, including the past.

When the character finally arrives at a decision, the reaction phase is over. In fact, the character’s decision to take some action propels us into the next step. Even if the character decides to ignore the problem, that’s an action. And as you’ll see, it’s going to fail. Because plot is all about trouble.

Action

At this point, the character has decided to take some action. The goal or purpose of the action is to fix the problem or complete some step along the way to fixing the problem. The character will either reach that goal or she won’t. When the goal is clear in the reader’s mind, they form a question: will the character solve the problem? It’s a clear yes or no proposition. And because the character is deserving and the problem is significant enough for the reader to care, the reader will hope the character succeeds and fear she might not.

If, however, you fail to make the decision and goal clear to the reader, then they won’t worry and hope as much as wonder what the hero is doing. Too much of that and we’re back to confusion instead of suspense. So make the decision and goal clear right up front.

If it’s a scene where the opposition is doing something to the character, then you make the opposition character’s goal clear. Think about Hitchcock’s bomb in the example above. The hero doesn’t know about it. But the reader does. The reader knows exactly what might happen. And because they know about the awful possibility, they can worry about it.

Let’s say the hero decided to call the apartment manager. Often, in our normal lives, the first action will solve the problem. In this case, the manager is in. The manager immediately calls the maintenance man who goes up stairs, finds the renters above left a sink running, turns it off, mops up the mess, and fixes the issue.

Problem solved.

That’s real life. We solve all sorts of problems on the first or second try in real life. We keep tension down. But with stories we don’t want to eliminate tension. We want to build it. The reader wants to worry for a good long time. And so the form has to be different. This is why problems in stories aren’t fixed so easily.

So what do you do?

You change the result of the action to something that maintains or builds tension. There are four types of consequences that can occur when you attempt to fix a problem.

- Yes: you fixed the problem.

- No: you didn’t fix it.

- No, but: no you didn’t fix it, but you did do or find something useful. For example, no, you didn’t find out who the murderer was, but you did find an important clue. Or no, you didn’t find the bad guy’s lair, but you did find a new ally. Or no, you didn’t capture the criminal, but you did get a license plate number.

- Yes, but: you fixed the problem, but now you have a bigger or different problem. For example, yes you killed the monster, but now you woke up the monster’s mumma and she’s twice as big and ferocious as he was. Or yes, you killed the monster, but he bit you and you are now infected with a virus that will turn you into a monster. Or yes, you escaped the prison facility, but the guards were alerted and are on your tail. Or yes, you killed the assassin sent after you, but now the bad guys know where you are. Or yes, you caught the thief, but now realize this means there was someone on the inside helping him. Or yes, you killed the killer robot (Mr. Incredible), but there’s some mysterious person watching you (and you begin to lie to your wife and then they bring you back and the monster just about kills you).

- No, furthermore: you failed to fix the problem, furthermore, you just made it worse. No, you didn’t kill the monster, furthermore, the beastie has now kidnapped your brother. No, you didn’t succeed in killing the king, furthermore, his guards caught you and now you’re in prison. No, you weren’t able to convince her to go on a date with you, furthermore, she thinks you were only asking so you could spy on her company. No, you weren’t able to convince your father to let you take the science class you so desperately need to get out of Nowhere-ville, furthermore, your father has cut off all your schooling privileges.

Which of those will make the problem harder to solve and increase a reader’s hopes AND fears for the character?

Not the first one. You cannot present a problem to your character and have them fix it on the first attempt. You can’t do this because then the story is over. There’s no hope and fear; there’s only “done” and they’re looking for a new story. You want to BUILD reader tension and curiosity and only release it after it’s grown to a sharp point. So a simple “yes” is out.

What about the others? A “no” will let you maintain tension. It doesn’t really change the story situation, but it can work. A “no, but” keeps the trouble in place but allows your character to make progress on solving the problem. This continues the fear and builts a bit of hope. That sounds good. A “yes, but” will allow the readers to hope for a while and then be plunged back into fear. That sounds good too. A “no, furthermore” will increase reader worry. We like worry, so that will work as well.

Of course, these kickers, the yes-buts and no-furthermores, will have more power if they also include an element of surprise. Not only does our hero experience a setback, but the situation has been altered in an unexpected that puts the readers on their heels—Crap! What will the hero do now?!

Again, the yes portion of the yes-but option can last for a scene or three. However, the other shoe must drop sometime. It might drop immediately. It might drop in the next scene when the villain reacts to what the hero just did. It might drop a few scenes later. But it must drop.

If the result truly is a yes, you must drop a new problem in its place. For every problem you solve, you need to raise at least one more or switch to another plot line (problem) that’s still active. There is no ideal length for the time between a “yes” and a “but.” There is only the principle that suspense depends on problem, and the longer you go without a problem, the more likely it is that your reader’s tension will decrease.

Of course, suspense is not the only delight stories deliver. If you ease up on the suspense and deliver a chapter or two of humor or wish-fulfillment, the reader might not notice or care. In fact, such a switch might be exactly what the reader needs. Nevertheless, the story can’t progress until we come back to the central problem. If readers complain that the story is slow or wanders, it just might be that you’ve strayed a bit too long.

Despite the variations just mentioned, for your story to continue, your character will enter the action with a goal and end up with trouble. In summary, the main parts of the action are:

- Goal

- Conflict

- Trouble

Okay, the last part really should be “Result,” but for most of the story it’s trouble, and so I’m sticking with it to emphasize the point. When we give our hero more troubles, we kick the story back up to problem, which leads to a reaction, which leads to action, which leads to more trouble, and another reaction, and around and around we go. We continue to kick the story around the cycle until the very end when the final answer to the final action is a big resounding YES! Or it’s an everlasting no and the readers close the book and weep, or blog about heartless authors, or, like I did once, rip the offending ending out, write a better one, and glue it in place.

Conflict & Surprise – The Cycle’s Dynamo

You’ll notice I’ve drawn the graphic with conflict and surprise as the dynamo in the middle that gives energy to the wheel. The role of conflict and surprise cannot be overstated. They imbue every part.

The inciting incident leads the character smack into conflict and surprise.

The action revolves around obstacles and conflicts and surprises. More importantly, it ends in a great dose of conflict and surprise—that’s the very definition of a yes-but and a no-furthermore. The hero starts out thinking his action will work and finds it doesn’t. Surprise!

Even in the reaction stage we can include conflict and surprise. Maybe after our team’s setback, they regroup and discuss what they’re going to do now. This is a fine time to allow the varying motives of those on the hero’s team conflict. Maybe this is the time when one of the people we rely on defects to the other side. Maybe it’s the time when we begin to really see the impact of the disaster that just occurred. It’s also a wonderful time for our hero to come to a surprising insight or make a surprising but logical decision. Or let one of the other characters make a surprising suggestion.

Through it all, this conflict and surprise keep the character at a disadvantage. And that keeps the reader hoping and fearing and wondering what in the world will come next and how will the character ever pull it off.

Look for how conflict and surprise work in the stories you love. And if you’d like, you can see it work in a fabulous sequence in _Life_, season 1, episode 3.

Here’s the setup. Charlie Crews is a detective who was sent to jail for a murder he didn’t commit. Being a cop in prison made him a target for many beatings, hence the yellow faded-bruise face. Eleven years later they found none of the DNA at the murder site was his. So they released him, and, as settlement for damages, gave him a bunch of money, and allowed him to be a cop again. He’s been partnered up with Dani Reese. Nobody really wanted him, but she’s had problems of her own and got stuck with him. Crews had a car in the first episode, geeked out about GPS and hands-off telephone (stuff his missed in prison), but the ex-con lawyer Crews has put up in his mansion ran it over with a tractor. He’s been riding the bus. In this sequence, Crews and Reese are looking for a guy named Manny Umaga who carjacked a man and his wife then shot the wife. In this sequence they go find where he is and then go get him.

Watch it and then read my comments below. It runs from minute 15:49 to 21:15.

1. Surprise. You walk into a dangerous car shop. What are you expecting? You know you’re going to meet hard characters. They’re not going to want to talk to you. There’s some danger here and, therefore, a bit of suspense. So we meet some hard characters. But did you see the surprising particulars of Buscando Maldito–his neck tattoos and hat? Wonderful and new (at least to me). Then before we can have the expected confrontation–surprise–Crews sees the car of his dreams. Then we get that wonderful exchange between him and Maldito and El Repitito. Total humor. Totally unexpected. Then Maldito suggests a posse? Not only is he willing to talk, but he suggests he goes with them? Did you notice as well Maldito’s surprising responses to Reese’s questions—no on-the-nose dialogue here. When going to get Umaga, more surprises. Flash bangs? Big honking Samoan running like that? Busts down the door? Takes Crews by the neck? Crews pulls his own knife? Surprise after surprise after surprise.

2. Conflict. Between Crews/Reese and guys in shop, Maldito and Crews about the car, Maldito and Reese (didn’t you love that bit about the airbrush), between Umaga and Crews, between Crews and setting. Then Crews and Reese (with the knife).

BTW, look at this sequence with the lens of the story cycle. If you watch just a little bit more, you’ll see it’s a classic yes-but trouble. Yes, they find Umaga (not without a lot of conflict), but the victim won’t identify him as the killer. And around the cycle the story goes again.

Now look at the last few scenes in the current story you’re reading. Is the author using conflict and surprise as tools to move the story around the cycle?

Plots that rock

We present readers with sympathetic and interesting characters who are dealing with significant hardships or dangers. But readers don’t want to worry for two seconds and then have their tensions resolved. They want to feel a rush of relief. And you can’t feel a rush unless there’s something major to feel relief from.

When does cold sweet water taste the very best?

Not when you’ve just drunk a gallon jug of it. Not when you’re swimming in a freezing lake full of it. No, water is mind-blowing when you’re so thirsty your tongue cleaves to the roof of your mouth, when the spittle has dried all around your lips, when you’ve been thinking about that drink for hours and the world seems to be nothing but heat and rock and dust.

When you’re bone thirsty dry, that’s when the first sip feels like the rapture.

The magnitude of the relief experienced in the resolution is in direct proportion to the stress that comes before it. So the more tense the reader is when they get to the resolution, the bigger the relief. If you’re delivering a mystery, the more puzzled the reader is, the bigger the insight.

In the beginning of the story we introduce the problem, raising a reader’s curiosity and interest. In the end we resolve the problem and satisfy the reader’s thirst. But it’s the wonderful middle where we build the thirst. With great middles, our story resolutions bang. Without them, they ho-hum and fizzle.

And it all revolves around making the story problem harder to solve. In fact, I’ve found that as long as I keep thinking about how to keep making things harder on my characters, the story scenes seem to line up and present themselves.

Now, we’re not done with plot just yet. In the next part, I’ll discuss the big picture of plot. It’s called structure. I’ll share why I think it’s more helpful to think about structure in the context of problem-solving, plot patterns, and Pareto elements than it is to talk about mythic journeys or rigid act numbers, proportions, and plot points. I’ll also break down at least one novel so we can see how an example of how everything we talked about works in practice.

In the meantime, if you think you might see other things that make a problem harder to solve or affect the story cycle, please add them in the comments.

Bonus 1 – A little Hitchcock

The following is an excerpt of an interview, presented in two parts below, between Alfred Hitchcock and Huw Wheldon. It was filmed for the BBC television program “Monitor” and was first broadcast on May 5, 1964. Watch it, keeping in mind the points made above. Of course, the purpose of sharing this isn’t to quote it like scripture. We don’t want to accept anyone’s model of story without thinking about it and testing it against our experience and observations. So listen and then let me know if you think his ideas are accurate.

Part 1

Part 2

Here’s another. “Movie Go Round,” 8 July 1966, Light Programme, Alfred Hitchcock talks to John Kennedy about the enjoyment of fear & ways of creating suspense (with reference to Vertigo).

By the way, if you enjoy Hitchcock, you’ll want to read Hitchcock on Hitchcock: Selected Writings and Interviews, edited by Sidney Gottlieb.

Bonus 2 – Development Questions

In the last part in this series, I’ll talk more about using suspense principles to generate story ideas, but you can start trying to apply the Pareto factors that have been discussed right now. Here are examples of productive questions you can ask yourself.

Problem

- What types of danger might my character face?

- Who’s in the most danger?

- Who stands to lose the most?

- What’s a stake?

- What are the character’s opportunities?

- What kinds of hardship might they face now?

- What are some potential mysteries in this world or with this problem?

- How can I make the problems more intense?

- Who might cause a lot of trouble in this situation?

- Why would the opposition want what they do?

Character

- What are some things that could make my character sympathetic?

- What are some things that could make my character deserving?

- What are some things that could make my character more interesting?

- What are some ways I could provide cast variety?

- Why types of people would be fun to put together?

Plot

- What types of obstacles does the character face?

- What are some things that can put my character at a disadvantage?

- What are some possible fun points of conflict inside the character, with people on the character’s team, with the opposition, and with other bit parts?

- What are some possible upsets the character can experience along the way?

- In what ways might the problem get worse?

- What are some surprises I can spring on my reader and character?

You don’t need to answer every question. Just take one and run with it listing as many options as you can. List out all the dumb cliches that come to mind. Don’t filter yourself. Dumb stuff works like manure on the garden of your mind. Cherish poop—it’s what makes flowers grow. As you generate your options, try to vary the nature of the solutions you come up. And try to think up some that are unusual. Sooner or later you’ll start coming up with ideas that spark.

Bonus 3 – An Invitation

I don’t want you to simply accept the model of the story cycle I’ve presented above. Please take some time when you next watch a TV episode or movie or read a novel and see if and how it works in the kind of fiction you love. You don’t have to break down the whole story if you don’t want to. Just do a scene or three. Then report back here what you found. You, me, and everyone who reads this will be better for your insights.

Parts in the The Key Conditions for Reader Suspense Series

-

Scene (coming soon)

-

Development Tips

This was a really great article. Lots of good advice, and a big help as I work on drafting my Nanowrimo novel.

I hope it’s clarifying and actually helps you feel like you have the big picture. Good luck on the nanowrimo!

Thanks John, these articles are helping me a lot. I have heard much of this information before from other sources, but you have a way of making it make sense.

I’m happy to hear that. When starting I felt so lost. I so very much wish I’d had someone help me with this stuff back then. It would have shaved years off my time to publication. In fact, I read SCENE & STRUCTURE by Bickham, and the next story I wrote won first prize in the Writers of the Future. Unfortunately, the creative process still eluded me. But at least I had a start. Of course, there was more to learn. There are things (like the objective) I think that Bickham leaves out. And there are some things he approaches in a way that was not helpful to me. But at least it was a start!

Close enough to win a cigar, but not quite to win the diamond ring. I’m encouraged to see omens around the Internet auguring structural writing instruction is coming back into fashion, hopefully, not at the expense of aesthetics.

This was a big post. Fourteen pages of goodness once I printed it off.

I appreciate these writing articles you are posting, John. I took them to work with me yesterday, and on my breaks I worked on my latest story. Lo and behold, just having the articles next to me and scanning them from time to time allowed me to solve a major character issue I had been having with the protagonist. Now he will be much more interesting and well-rounded; more realistic and sympathetic.

Thank you for the inspiration.

Dannyboy,

Yes! So happy to hear they’re helping. This one was indeed a big old momma. I spent time writing it that I should have spent on Dark God’s Glory. But I keep talking about this stuff in my workshops and wanted a resource for folks who don’t make their living taking shorthand notes. I also wanted to update my model for myself. In fact, part of my process is to revisit the big picture before I dive into new projects. So these posts are helping me as well as I work through the pre-draft stuff invovled with my next novel.

I will also say that the updated Story Cycle diagram makes me happy just to look at it. The addition of the “no, but” result and the change from “disaster” to “result” were helpful to me and removed a few snags that were bugging me. And I luv those Hitchcock clips and the article I was able to PDF from good housekeeping.

BTW, although you may hate me for it and I should probably mark it someway, I am editing these. So I expanded the intro to part 1 yesterday. And I updated the end of characters with additional reading today. As well as updating the bit about the “specific” intensifier.

Great stuff John! I learned a lot from this post, especially your story cycle diagram. Kind of reminds me of a programming flowchart. Were you a programmer in your past (non-writing) life?

I did get my masters in accounting and information systems and currently work for an ERP software company. So I’ve done flow diagrams, although I’m not a techie. That cycle just needed a visual.

You know what you should do with these?

A) Try to get this published

B) Get someone with some free time and a little knowledge to make this into an e-book and sell it on Amazon for a really low price. In fact, with a tiny bit of a learning curve, you could even use something like http://code.google.com/p/sigil/ to do it yourself for free. I’m not entirely sure how it works, but I’m fairly certain that Amazon will let anyone put up an e-book as long as you give them a cut of the profits. Heck, I’d buy it when it’s all done, that’s for sure!

A) would be great, but if nothing else, B) would get you some compensation for all the hard work you’re putting into these posts. Just a thought.

That’s a good idea, Bryce. When I finish them, I’ll look into doing just that

Christine Amsden is a fantasy and romance writer. I just read her post The Quest for the Three Magic Words.

I thought it was great, not only because I enjoy love stories, but also because it illustrates what happens when you don’t provide believable and gnarly obstacles/conflict. Suddenly, the story fails to elicit reader tension about what MIGHT happen. I wouldn’t take from this that you can never have a three-word problem in a love story. That might be a matter of audience taste, as Christine points out. The big insights are her points about obstacles.

I was exposed to Larry Brooks and Dan Wells teachings on story structure when I first really began to study plotting specifically. However, I liked your model here as well with the Inciting Incident, problem, reaction, action, and the resolution (or more trouble with the yes, but, or no, and etc) as it seems to break plotting down into its most basic fundamentals.

I heard you talk about all this at Life the Universe and Everything symposium this February 2011, and also on the videos that Steve (he’s a writer’s group buddy of mine) did for you on “How to Write a Story that Rocks,” but I’ve looked over a lot of stories (movies in particular) that worked very well with plot structures I had learned, so when you said that the plot systems didn’t work it confused me. I thought the plotting structure I learned clearly did, but thinking back I was using both of them rather more as principals loosely followed rather than set rules (like having to have your hero almost die in every story, or near death, etc).

Oddly enough, I recently became stuck on my fantasy novel sometime after and couldn’t seem for figure out what was wrong even with the plotting structure points that I learned.

Your fundamentals of plotting helped today, as I realized on a more basic level that some of my problems for the protagonist were failing to create suspense, danger (etc) in the story. There was still some danger, just not enough of it surrounding them–I lost the “zing” as you call it somewhere. Some of my results of their attempts to solve the problem weren’t detailed enough, or didn’t have additional compounding problems or consequences along the way, and the plotting systems I learned didn’t have methods to show how to come up with or use more problems in-between the story plot points.

Using the plotting structure lesson you’ve given I was able to break through. Even though I haven’t figured out the rest of the story yet I can at least diagnose problems quicker to see what needs to be brainstormed, or outlined with the conflicts of the story to help it feel compete and “zing” me.

The plotting structures I learned help at times like an overview and presentation for my stories, as well as what has worked for many popular stories (the ones I’ve looked at anyway), but can fail to describe every type of possible story, and whose proportions are not always spot on (thus the percentages and close approximations), and for me at least they failed to help work out some of the connective story tissue (problems, results, complications, etc) BETWEEN the major plot points (and I think often there needs to be a lot more). Followed too closely, like you said, plotting systems can become a barrier to plotting rather than a guide–I’m pretty certain that’s why I hit a bit of a snag.

I’ve found it useful also sometimes to just free-write when I get into those situations as it seems to debunk whatever jam I am in, which for me has been hard because I know most of the free-writing exercise won’t make it to the final draft

I’ve probably echoed here much of what you’ve already said, but I thought it might be helpful for others to hear another person’s perspective in relation not only to your own material on plotting, but a couple of others too.

Happy writing everyone (and John).

Nathaniel,

Thanks for your thoughtful post. The key issue I have with structure models is that (a) they very often divorce form from function and (b) ignore the many options that work. When you do that, even if you don’t mean to, you’re left with a rigid prescription that often doesn’t apply.

I simply find the Bickham/Swain approach much more practical and flexible all the way down to the scene level. And I think that’s becaue it’s married to the function.