Even after you choose a genre, you still need to develop ideas for character, setting, problem, plot, and text.

What do you do? How do you develop those ideas?

The first thing you do is hunt zing.

Feeding the beast

Zing is any idea that turns you on, sparks your imagination, or stokes your desire. Zing tingles your cool meter. Dude, yes, ah, oh baby, man-o-man, great oogily boogily–these are all common responses when you come across these types of ideas.

Most zings are small tingles. Sometimes they’re zaps. Rarer still are the freaking gigawatt monsters that shake you about and leave you breathless. But I’ve found I can’t wait for those. Or maybe I should say that they often come only after I’ve caught smaller prey.

Your imagination is a beast. Feed it and it will get up and terrorize the neighborhood on its own accord. Starve it and it will lie there like a gigantic dust mop and gather flies.

Nothing in, nothing out.

YOU MUST FEED YOUR IMAGINATION!

Some of us might feel we don’t have much to feed our imagination. Most of us are not Ann Franks or CIA agents or little old ladies caught in terrorist plots. But we don’t have to be.

I once taught teen writers workshop where we met one day each week for three weeks. During the first class I introduced zing and told the students they were to hunt for 10 zings each day.

They were dismayed. They groaned. Ten? Was that possible?

The next week all of the students came back bubbling about all the things they’d found. One of them said it had changed things for her: her world which had been relatively hum-drum was suddenly filled with the cool. The other students agreed.

We all are limited by what we can perceive and focus on. Our working memories are so small. And so it’s easy to focus on so many mundane business-of-life things and miss the wonderful show of lights that goes on around us.

This is what hunting for zing does for you. It quite literally changes your world.

Be a hunter.

Capture the zing.

This is the first step. You have to gather interesting material. Lots of it. Which means you must turn your zing sensors on.

This is the first step. You have to gather interesting material. Lots of it. Which means you must turn your zing sensors on.

What do I mean by this?

Open your eyes and ears and heart. Be on the look out. When something cool comes along, capture it. Use scratch paper, the back of a receipt, get a notebook, a folder file, a camera, a sketchbook. Just capture it when it comes. And it will come.

Most of the ideas are never used, but unless you capture them, i.e. notice them, you won’t get the ones that do develop into something special. For many of us writing them down is the way to really give them the attention they need. I promise you: these little scraps and snippets have a way of combining at the oddest moments, and suddenly you have more than an itty-bitty old zing, you have a freaking power plant!

The Drag Net

Having your sensors on is like deploying a drag net—it catches whatever swims into it. One of the benefits of this is that you get ideas you’d never in a million years come up with on your own. Here are some random things I caught in my drag net.

Some people actually raise chickens in their apartment (from a book I happened to pick up while browsing a section of the library).

Hum, what if my character’s neighbor does that? What if it’s his kooky sister? Maybe his wife decides they need to be more self-sufficient. Or maybe she’s told a neighbor she’d take care of her chickens.

A girl was sold to cover her father’s debts (while reading an article about ancient history)

Could that happen today? How would that work? What if it was someone else kidnapping a girl to pay off debts?

“The monkey, which costs $15,000, is what Truelove envisions as the ultimate SWAT reconnaissance tool. Since 1979, capuchin monkeys have been trained to be companions for people who are quadriplegics by performing daily tasks, such as serving food, opening and closing doors, turning lights on and off, retrieving objects and brushing hair. Truelove hopes the same training could prepare a monkey for special-ops intelligence.” (From an online newspaper that’s sent to me each week)

A SWAT monkey? Come on! Could this primate be put to nefarious purposes? What if he stole something incredibly valuable? What if a major thief uses them? What if it’s a boy in the neighborhood?

There’s a guy who lets his toenails grow to horrible lengths; they look like claws. It’s incredibly disgusting (Something a friend said about one of his friends in an email)

Does your main character have a partner? Someone they work with in the office? A mate in their medieval army squad?

GARDEN GROVE (CBS) — An Albertson’s supermarket on Harbor Boulevard was evacuated Monday after a burglary suspect fell through the ceiling to the ground near a cash register.

What if that’s your main character? What was he doing stealing copper? Maybe he was forced to?

Headline in Daily Mail Reporter: Ghurka kills 30 Taliban. ‘I thought I was going to die… so I tried to kill as many as I could’: Hero Gurkha receives bravery medal from the Queen. Corporal Dipprasad Pun defeated more than 30 Taliban fighters single-handedly. Used the tripod of his machine gun to beat away a militant after running out of ammunition.

Could this be used as a scene in the story? What about the tripod business?

In this May 2011 security camera frame grab provided by the Stevens County Sheriff’s Office, dogs are seen at the home of a resident near Deer Park, Wash. A pack of dogs has killed about 100 animals in the past three months while eluding law enforcement and volunteers in northeastern Washington state. The killings are happening in a wide area of mountains and valleys west of Deer Park, a small town about 40 miles north of Spokane, authorities said. (AP Photo/Courtesy of the Stevens County Sheriff’s Office)

What if these guys are roaming the neighborhood where your character lives? What if it’s a fantasy story and these are not just dogs? Are they bewitched? Trolls? Something come in from the woods?

As far as pictures go. How about this gal? Would she fit in a romantic comedy? A murder mystery? What if she went missing? What if someone kidnapped her son?

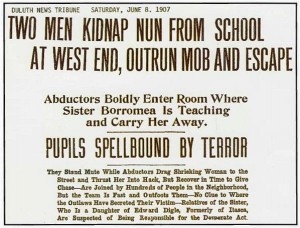

What about this newspaper clipping? Click on the image and read the fine print.

All you have to do is start asking questions of these zings and they can’t help but produce character, setting, problem, and plot.

Deploy your drag net.

Do it now.

Hunting With A Purpose

Even though your drag net is out, you cannot rely on it to deliver all the ideas you need. Very often you need to go hunting with a purpose. In fact, whenever you have development objectives, you’ll be on the lookout for that thing you need to develop.

Let’s say you want a funny and new fight scene in your story. Look at the stuff above.

- A fight including that gal in the wedding dress?

- One in the space the copper thief fell from?

- How about one in a chicken apartment?

Maybe you need a new love interest.

- What if she’s the copper thief?

- What if she’s out hunting the wild dogs?

- Maybe he’s the guy who kidnapped the nun?

Do you see? When you have a purpose, you look at the things you come across with a different lens.

But you might need to be a bit more active in your hunt. You might need to do some things to find what you’re looking for. I’m talking about directed research.

An Example

I attended Orson Card’s literary boot camp. He had us take a day and develop five story ideas (or seeds) which we were to write down on ONE side of a 3×5 card (hum, sounds a bit like the story setup we talked about in the previous blog).

2 of the cards were for story ideas we developed from research conducted at Barnes & Noble or in a library

2 were for ideas developed from a drag net of events or curious things I saw that day

1 card was for an idea developed from an interview with someone.

The assignment was to look at things as a writer, to exploit what I see as a writer. On the card we were to tell a story. The fundamental idea–what happens and why. Just the idea and some events. The space limint on a 3×5 card forces you to think of story and NOT the writing.

Oh, and the research was supposed to be for something we didn’t find interesting, which meant we didn’t know squat about it.

I researched Iroquois Indians, women who did crazy things like going over Niagra Falls in a barrel, and some other crap I can’t remember. I also read a bit about an American Indian in 1614 who was stolen as a slave, taken to Spain, got his freedom, went to England and then back home.

I interviewed two women in a music box shop and worker in a Thomas Kindcade art gallery. The gallery gal was blonde and rode Harleys. Had tattoos. What in the world was she doing in a THOMAS KINCADE gallery?

I used the Elizabeth Smart poster (abducted girl) and an empty music box as my curious things.

I worked from 5PM until 9PM on the ideas and never really got anything. Went up on a hike up Rock Canyon still thinking about it. Saw a cave; evening came; the canyon was beautiful. Marvelous. Almost stepped in a snake. Worked and worked on the music box idea and the kidnapping idea. More on the music box.

No ideas really pulled me.

Next morning I woke at 6 AM and started thinking. Decided I had no time AND I WOULD HAVE TO FOLLOW NELLIE’S [my wife] ADVICE and simply go with what I had. I made a decision and go with it even though I didn’t really feel it inside.

During class, someone else talked about bone magic. It was cool! I stole the bone magic idea and crossed it with the Iroquois stuff I’d looked at and suddenly started liking my story a whole lot more. Decided the tribe that lost their only bone breaker (that’s how the magic was obtained) in a raid (he was sold to the French as a slave) and sent out a woman who knew French and a warrior to retrieve him.

The next day I was supposed to write the story. I found I didn’t really want to write that one. Spent all day at the library reading juveniles and encyclopedias on Iroquois and Eastern Indians. Read for 5 hours then began to try to write.

Now, let me stop here.

Through my directed research I had collected gobs of zing. There were Indian names like “Handsome Lake” and “He Who Keeps Them Awake,” the fact that the Iroquois had a peace sachem (leader) and a war leader. The peace leader was a woman and chose the male war leader. I had stories about abducted Whites and Indians being sold into slavery and escaping. I read about men purchasing Indian wives. I added tidbits I knew from the Netherlands and Bible. It went on and on and on.

I had TONS of cool material to work with because I’d actively gone on the hunt for it.

If you look back as the example I shared about the golem story in the previous post, you’ll see I researched golems and Croatia and found TONS of cool material. I added to that other tidbits I already had. And the result was massive zing.

So what happened with that Iroquois story?

Well, I finished it, and it went on to sell multiple times. It’s called “Bright Waters”. Here’s how it starts. But the thing to remember is that it all started with the directed hunting for zing.

Bright Waters

In the spring of 1718 Jan van Doorn returned to his log house with a load of molasses, flour, and a fine green dress for his new wife. He found she had run out on him and taken half of his goods with her.

She was the second wife he’d bought. And the second one to run away before a season was out.

Her name was Woman With Turtle Eyes, an older Huron of 23 years. He had thought an older woman would be more stable than the girl he purchased the first time. Besides, she said she wanted him to buy her.

Jan didn’t understand how the men in the settlements courted and kept their women. And it couldn’t be because he was ugly. He’d seen plenty of ugly men marry. The only ones that seemed to have any interest in him were the whores at Fort Montreal, and when he’d given in to his urges that one cursed time, they took far more from him than his money.

There was nothing to do about Woman With Turtle Eyes. If he hunted her down, she’d just run away again. He could beat her, but she’d run nevertheless. Besides, her theft meant he’d have to start working his old claim, and there were precious few weeks before the beavers began to shed their winter coats. No, there was nothing to do but fold up the dress and put it in the cedar chest.

He looked down upon the dress for a few moments admiring the fine, shimmering cloth. Then he closed the lid.

That night Jan cooked himself a meal of kale and old potatoes. When he finished, he rubbed deer urine onto his traps to prepare them for the morrow. Then he went to bed.

Remember: zings are almost always small. Don’t be looking for the ONE killer idea. Usually the killer story is made up of a bunch of smaller zings.

“What generally happens is that I’ll be reading up on some topic just for entertainment — spies, pirates, the Romantic poets, mountain-climbing — and I’ll notice a few indications that the situation might do as the basis for a novel. At that point I declare that this isn’t recreation anymore, it’s research. So I start reading lots of books and articles on the subject, even if they’re not entertaining. And I follow any side-paths that show up — for one book, Tarot led to Poker which led to Las Vegas which led to famous gangsters. And while I’m reading all this, I’m looking for bits that are “too cool not to use.” When I’ve got a dozen or so things that are too cool not to use, then I’ve got — obviously — a dozen elements of the eventual novel.” ~ Tim Powers

Your Zing, Not Mine

Again, you don’t want any old idea. You want good ones. So how do you recognize a good idea?

YOU FEEL IT!

Good ideas carry current, they spark your interest, they tug your heart strings, they turn you on. This is what I’ve learned: a good idea is like an electric jolt. Sometimes it’s very small, sometimes it’s overpowering. It’s the feeling of “cool,” “whoa,” or “oh, boy, this has possibilities.”

But notice I said they spark your interest.

You’re not looking for what turns me on. For you to write a story, you have to follow your zing, not mine or your friend’s or your mentor’s.

The trick is finding your zing and then sharing your zing with people who have similar tastes.

Where to find zing

There are a few places where I seem to find TONS of zing. Maybe they’ll be productive for you.

Source 1: Other stories

I get an unlimited supply of ideas from other stories. Here are a number of sources.

- The news

- History

- Friends and acquaintances

- My past

- Strangers

- Scripture

- Gossip

- Fairy tales

- Poems

- Movies

- TV programs (fiction and non-fiction)

- Summaries of actual court cases

- Novels

- Magazines

- Biography

- Interviewing a relative or friend for their life story

Source 2: Snippets of life

Every week I run across interesting conversations, lines, facts, events, images, and people. These things aren’t stories but they can be used to enhance or generate one. In fact, part of the joy of writing is finding ways to incorporate the cool things I encounter into the current story. There are many places where I find these snippets of life:

- People I know or talk to

- Science

- History

- Poetry

- The Discovery Channel and its many cousins

- How-to books, videos, tapes

- Current or historical issues

- Books on how people used to live

- Photographs of other lands and cultures

- People I see (The hero of my Writer’s of the Future story was based on a transient I picked up one night who lived in a storage space at the town’s used bicycle shop)

- Learning about other people’s professions

- Trying new things

Source 3: Research

This is just another way of coming across stories, facts, events, people, and trying new things, but it’s more directed.

This is just another way of coming across stories, facts, events, people, and trying new things, but it’s more directed.

- Do it

- Visit it

- Talk to those who have done it or been there

- Watch movies about it

- Read about it, starting with Juveniles & Encyclopedias and then moving to thicker texts

When I moved up into the hinterlands of Utah, I found out they had an annual local testical festival. As a regular joe I might have gagged and moved on. As a zing hunter, I couldn’t afford to do that.

No, they do not taste like chicken.

They do taste like something many people find delicious. But I’ll let you identify what that is with a little research of your own.

When you get a chance to try something new–try it. You get marvelous details, wonderful ideas. And you just might find you enjoy life a little bit more. Or at least be grateful you’re not trapped in a coffin.

I was writing a scene for one of my books, where a secondary character accidentally locks himself in a casket. Not having experienced such a tragedy, I began winging that thread on imagination alone. But the scene simply wouldn’t jell. When I finally finished the first draft and read it, it felt two-dimensional. So I wrote it again. It still stank. By the third draft my frustration level had peaked, and I shoved my chair away from the computer, knowing there was only one solution to this two-dimensional problem. I would have to experience it. Now you would think a logical person would take into consideration that the number of readers who’d actually been trapped in a casket was minimal enough to make the whole issue moot. Then again, we’re talking about a rational person…I’ll tell you, I’ve pulled some crazy stunts before, all in the name of research, but this one ranks in the top three. ~Deborah LeBlanc

Nobody can copyright an idea or technique

Don’t worry about stealing ideas from someone else or using a technique you find in another story. Don’t worry that something’s already been done. What you want to avoid is copying the writing. But take any idea or technique and run with it–in your own direction. Remember: The Terminator & Back to the Future have the same premise but are two totally different stories. So go wild.

Be a hunter.

Capture the zing.

Start gathering your writing material today.

For more in this series, see How to Get and Develop Story Ideas